Traducción de Gerardo Yvan Morales

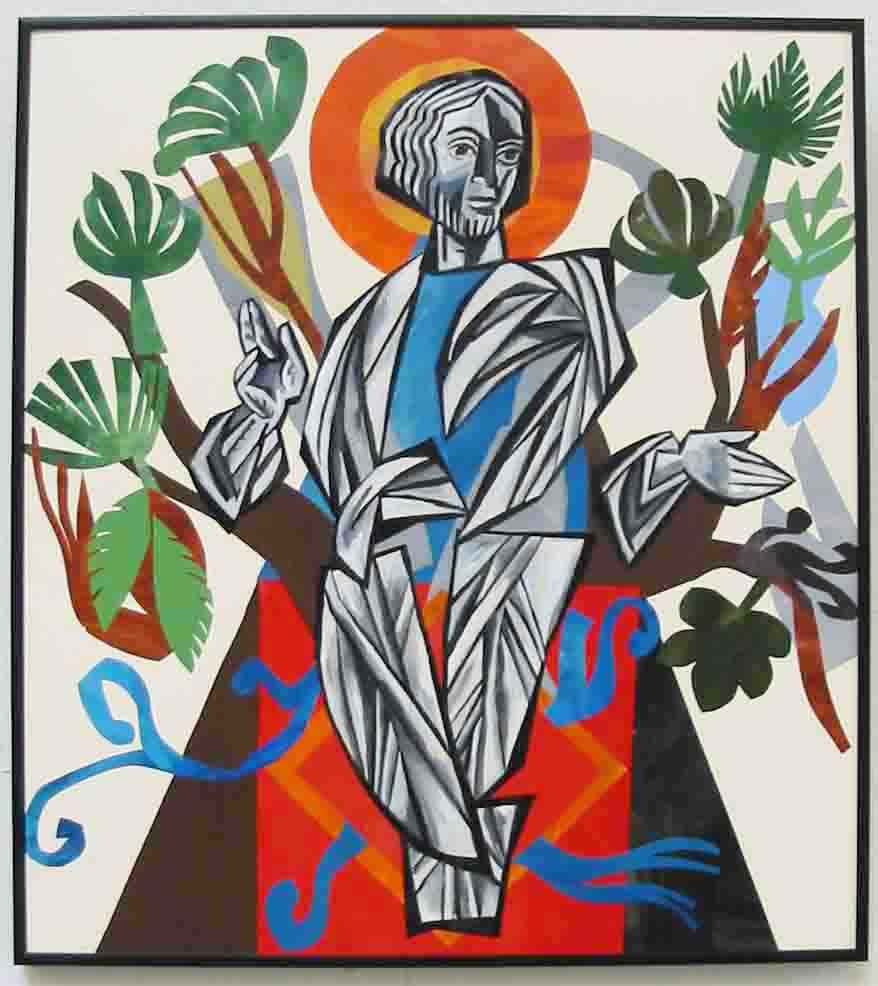

Cada viernes de Cuaresma meditamos en las Estaciones de la Cruz. Contemplamos a Cristo crucificado, en representaciones artísticas de la Pasión y en el ojo de nuestra mente. Me gustaría pasar un tiempo esta noche reflexionando sobre otras formas en que podemos ver a Cristo crucificado. ¿Dónde está El Señor crucificado entre nosotros? ¿Cómo lo reconoceremos cuando lo veamos? ¿Cómo podemos sintonizarnos con nuevos tipos de visión mientras hacemos nuestro viaje hacia la alegría de la Pascua?

Un teólogo que reflexionó profundamente sobre estas cuestiones fue uno de los autores del Nuevo Testamento, Pablo. Viajó por las ciudades del mundo mediterráneo en el período comprendido entre el 30 y el 64 DC, justo después de la vida terrenal de Jesús. Pablo se detenía en los hogares para predicar el evangelio y edificar pequeñas comunidades. A menudo enviaba cartas a las comunidades que había fundado, ofreciendo aliento, consejo y (cuando era necesario) corrección. Las cartas de Pablo también nos muestran la naturaleza de su relación con Cristo crucificado.

Each Friday in Lent we meditate on the Stations of the Cross. We behold Christ crucified, in artistic representations of the Passion and in our mind’s eye. I’d like to spend some time tonight reflecting on some other ways we might see Christ crucified. Where is the crucified Lord already in our midst? How will we know him when we see him? How can attune ourselves to new kinds of seeing as we make our journey toward the joy of Easter?

One theologian who thought deeply about these questions was the New Testament author Paul. He traveled throughout the cities of the Mediterranean world in the period between 30 and 64 CE, just after the earthly lifetime of Jesus. Paul stopped in households to preach the gospel and build up small communities. Often he would send letters back to the communities he had founded, offering encouragement, advice, and (when necessary) correction. Paul’s letters also show us the nature of his relationship with the crucified Christ.

(1) La propia historia de la vida de Pablo reveló el poder transformador de la crucifixión de Cristo. Probablemente esté familiarizado con el relato del llamado de Pablo, a veces llamado su conversión. Tres veces en los Hechos de los Apóstoles, leemos acerca de Pablo, un judío devoto que trató de acabar con este nuevo movimiento que afirmaba que Jesús era el Mesías judío prometido. Persiguió a los creyentes en Cristo hasta que un día, en el camino a Damasco, escuchó una voz que le preguntaba: “Saulo, Saulo, ¿por qué me persigues.” El orador se identificó como Jesús, y Pablo comenzó a creer que Jesús verdaderamente era el Cristo, el Hijo de Dios. Pablo describe el evento en su carta a los Gálatas: “Dios, que me apartó desde el vientre de mi madre y me llamó por Su gracia, tuvo a bien revelar a Su Hijo en mí para que yo lo anunciara entre los gentiles, no consulté enseguida con carne y sangre” (Gálatas 1:15-16). Y así, Pablo se convirtió en evangelista, un misionero que difundía el evangelio sobre la crucifixión y resurrección de Cristo.

(1) Paul’s own life story revealed the transformative power of Christ’s crucifixion. You are probably familiar with the account of Paul’s call, sometimes called his conversion. Three times in the Acts of the Apostles, we read about Paul, a devout Jew who tried to stamp out this new movement claiming that Jesus was the promised Jewish Messiah. He persecuted Christ-believers until one day, on the road to Damascus, he heard a voice asking, “Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting me?” The speaker identified himself as Jesus, and Paul began to believe that Jesus truly was the Christ, the Son of God. Paul describes the event in his letter to the Galatians: “God, who had set me apart before I was born and called me through his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son to me, so that I might proclaim him among the Gentiles” (Gal 1:15-16). And so Paul became an evangelist, a missionary spreading the gospel about Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection.

En el camino, Pablo enfrentó oposición, desde el despido y la incredulidad hasta el encarcelamiento y la violencia absoluta. En 2 Corintios ofrece un catálogo de todas las formas en que sufre:

“Cinco veces he recibido de los judíos treinta y nueve azotes. Tres veces he sido golpeado con varas, una vez fui apedreado, tres veces naufragué, y he pasado una noche y un día en lo profundo. Con frecuencia en viajes, en peligros de ríos, peligros de salteadores, peligros de mis compatriotas, peligros de los gentiles, peligros en la ciudad, peligros en el desierto, peligros en el mar, peligros entre falsos hermanos; en trabajos y fatigas, en muchas noches de desvelo, en hambre y sed, con frecuencia sin comida, en frío y desnudez.” (2 Cor 11, 24-27).

Sin embargo, su propio sufrimiento solo lo hizo sentir más conectado con el Cristo crucificado. Cristo sufrió, y Pablo también sufre, a imitación de Cristo. A los Gálatas les dice: “yo llevo en mi cuerpo las marcas de Jesús.” (Gal 6,17). La profesora del Nuevo Testamento Margaret Mitchell sugiere que Pablo pensó en su predicación como un "espectáculo multimedia": explica el evangelio en palabras, pero también afirma que representó a Cristo a través de su propio cuerpo: "ustedes, ante cuyos ojos Jesucristo fue presentado públicamente como crucificado!” (Gálatas 3:1).

¿Dónde encontramos predicadores poderosos como Pablo, aquellos que comparten las formas en que la crucifixión salvadora de Cristo ha transformado sus vidas? ¿Hay testigos en su comunidad cuya pasión por el evangelio trae la crucifixión ante sus ojos de una nueva y más vibrante manerasdf? Busquémoslos a medida que avanzamos en la Cuaresma.

Along the way Paul faced opposition, from dismissal and disbelief to imprisonment and outright violence. In 2 Corinthians he offers a catalog of all the ways he is suffering:

“Five times I have received from the Jews the forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I received a stoning. Three times I was shipwrecked; for a night and a day I was adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from bandits, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers and sisters; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked” (2 Cor 11:24-27).

Yet his own suffering only made him feel more connected to the crucified Christ. Christ suffered, and Paul also suffers, in imitation of Christ. He tells the Galatians, “I carry the marks of Jesus branded on my body” (Gal 6:17). New Testament scholar Margaret Mitchell suggests that Paul thought of his preaching as a “multimedia show” – he explains the gospel in words, but he also claims that he represented Christ through the medium of his own body: “It was before your eyes that Jesus Christ was publicly exhibited as crucified!” (Gal 3:1).

Where do we encounter powerful preachers like Paul, those who share the ways that Christ’s saving crucifixion has transformed their lives? Are there witnesses in your community whose passion for the gospel brings the crucifixion before your eyes in a new, more vibrant, way? Let’s look for them as we move through Lent.

(2) Pablo también encontró a Cristo crucificado en los rostros de los que sufren. Los creyentes de Cristo en Galacia luchaban con preguntas sobre su fe y cómo practicarla (¿deben ser circuncidados los gentiles? ¿Los no judíos deben seguir las leyes de la Biblia hebrea?). Pablo reconoció su lucha y se presentó como una madre embarazada que arriesga su cuerpo por la comunidad: “Hijitos míos”, dice, “por quienes de nuevo sufro dolores de parto hasta que Cristo sea formado en ustedes…” ( Gálatas 4:19). De manera similar, les dice a los tesalonicenses: “… Más bien demostramos ser benignos entre ustedes, como una madre que cría con ternura a sus propios hijos. Teniendo así un gran afecto por ustedes, nos hemos complacido en impartirles no solo el evangelio de Dios, sino también nuestras propias vidas, pues llegaron a ser muy amados para nosotros.” (1 Tes 2, 7-8). Su preocupación maternal significa que está presente con los demás en su dolor, así como las mujeres al pie de la cruz estuvieron presentes con Jesús en su dolor.

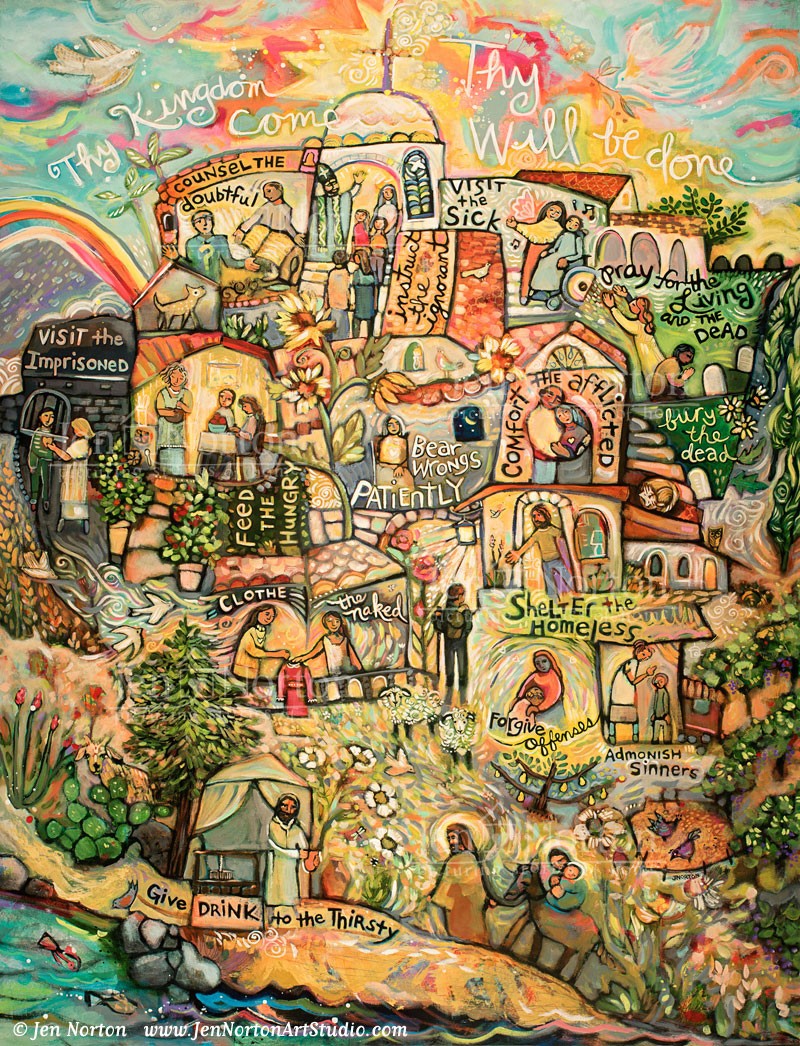

El ejemplo de presencia compasiva de Pablo puede conectarse con las obras de misericordia corporales, un componente importante de la Enseñanza Social Católica. Los cristianos estamos llamados a tender la mano a los que sufren, a reconocer en ellos el sufrimiento de Cristo y a encarnar la compasión de Cristo por ellos. La parábola de las ovejas y las cabras en el evangelio de Mateo, capítulo 25, explica que en el juicio final, Jesús, el Hijo del Hombre, nos pedirá cuentas. Él usará como base para juzgar nuestro cuidado por los que sufren: ¿alimentamos al hambriento, damos de beber al sediento, recibimos al extranjero, vestimos al desnudo, cuidamos al enfermo y visitamos a los encarcelados? Jesús proclama: “En verdad les digo que en cuanto lo hicieron a uno de estos hermanos Míos, aun a los más pequeños, a Mí lo hicieron” (Mt 25,40).

(2) Paul also encountered the crucified Christ in the faces of those who are suffering. The Christ-believers in Galatia were struggling with questions about their faith and how to practice it (should Gentiles be circumcised? do non-Jews need to follow the Hebrew Bible laws?). Paul recognized their struggle and presented himself as a pregnant mother putting her body on the line for the community: “My little children,” he says, “for whom I am again in the pain of childbirth until Christ is formed in you…” (Gal 4:19). He similarly tells the Thessalonians, “…we were gentle among you, like a nurse tenderly caring for her own children. So deeply do we care for you that we are determined to share with you not only the gospel of God but also our own selves, because you have become very dear to us” (1 Thess 2:7-8). His maternal concern means that he is present with others in their pain, just as the women at the foot of the cross were present with Jesus in his pain.

Paul’s example of compassionate presence can be connected to the corporal works of mercy, an important component of Catholic Social Teaching. We Christians are called to reach out to those who suffer, to recognize Christ’s suffering in them and embody Christ’s compassion for them. The Parable of the Sheep and the Goats in Matthew’s gospel, Chapter 25, explains that at the final judgment, Jesus the Son of Man will call us to account. He will use as a basis for judgment our care for those who suffer – do we feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, welcome the stranger, clothe the naked, care for the sick, and visit those who are imprisoned? Jesus proclaims, “Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me” (Mt 25:40).

Tanto Pablo como Jesús nos invitan a ver que Cristo crucificado está presente en todo lugar donde hay sufrimiento. ¿Dónde ves el rostro de Cristo, the face of Christ, en nuestra ciudad? ¿En nuestro mundo? ¿Cómo puedes estar presente con aquellos que están sufriendo? Hoy, esta semana, ¿cómo puedes ofrecer atención compasiva?

(3) Finalmente, Pablo nos recuerda una importante enseñanza cristiana: el sufrimiento no es el final para ninguno de nosotros. Así como la crucifixión de Cristo condujo a la resurrección, nuestro sufrimiento conducirá a la transformación. En su segunda carta a los Corintios, la misma carta en la que enumera todas sus muchas penalidades, Pablo también escribe: “Afligidos en todo, pero no agobiados; perplejos, pero no desesperados; perseguidos, pero no abandonados; derribados, pero no destruidos. Llevamos siempre en el cuerpo por todas partes la muerte de Jesús, para que también la vida de Jesús se manifieste en nuestro cuerpo.” (2 Cor 4, 8-10).

Paul and Jesus both invite us to see that the crucified Christ is present in every place where there is suffering. Where do you see the rostro de Cristo, the face of Christ, in our city? In our world? How can you be present with those who are suffering? Today, this week, how can you offer compassionate care?

(3) Finally, Paul reminds us of an important Christian teaching: suffering is not the end for any of us. Just as Christ’s crucifixion led to the resurrection, so our suffering will lead to transformation. In his second letter to the Corinthians, the same letter where he lists all his many hardships, Paul also writes, “We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed; always carrying in the body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be made visible in our bodies” (2 Cor 4:8-10).

A medida que hacemos nuestro viaje de Cuaresma, un viaje de arrepentimiento y disciplina a veces doloroso y desalentador, el recordatorio de esperanza de Pablo puede ayudarnos a transformar nuestro pensamiento. Incluso nuestro propio sufrimiento puede llevarnos a un encuentro íntimo y poderoso con el Cristo crucificado en nuestro interior. El Santo Papa Juan Pablo II expuso algunas sugerencias en su carta apostólica de 1984 Salvifici Doloris (Sobre el significado cristiano del sufrimiento humano). Él explica: “Como resultado de la obra salvífica de Cristo, el hombre existe en la tierra con la esperanza de la vida eterna y la santidad. Y aunque la victoria sobre el pecado y la muerte realizada por Cristo en su Cruz y Resurrección no abolió el sufrimiento temporal de la vida humana, ni liberó del sufrimiento toda la dimensión histórica de la existencia humana, sin embargo arroja una nueva luz sobre esta dimensión y sobre cada sufrimiento: la luz de la salvación. Esta es la luz del Evangelio, es decir, de la Buena Noticia” (Salvifici Doloris 15) Todo nuestro sufrimiento se realiza a la luz de Cristo que pone fin al mal y a la muerte, que nos libera para la vida eterna. No sólo eso, Cristo está presente con nosotros en nuestro sufrimiento: “Y Cristo por su propio sufrimiento salvífico está muy presente en todo sufrimiento humano, y puede actuar desde dentro de ese sufrimiento por los poderes de su Espíritu de verdad, su Espíritu consolador” (Salvifici Doloris 26).

Pablo recordó a los Filipenses que Jesús “transformará el cuerpo de nuestro estado de humillación en conformidad al cuerpo de Su gloria” (Filipenses 3:21). Cuando vemos a Cristo crucificado, en los demás o en nosotros mismos, ¿podemos aferrarnos también a la esperanza? A lo largo de nuestro camino de Cuaresma, ¿podemos fijar nuestra mirada en la crucifixión y su promesa transformadora de resurrección?

As we make our Lenten journey, a journey of sometimes painful and discouraging repentance and discipline, Paul’s reminder of hope can help us transform our thinking. Even our own suffering can bring us to an intimate, powerful encounter with the crucified Christ within. Saint Pope John Paul II laid out some suggestions in his 1984 apostolic letter Salvifici Doloris (On the Christian Meaning of Human Suffering). He explains, “As a result of Christ's salvific work, man exists on earth with the hope of eternal life and holiness. And even though the victory over sin and death achieved by Christ in his Cross and Resurrection does not abolish temporal suffering from human life, nor free from suffering the whole historical dimension of human existence, it nevertheless throws a new light upon this dimension and upon every suffering: the light of salvation. This is the light of the Gospel, that is, of the Good News” (Salvifici Doloris 15) All our suffering takes place in light of Christ who brings an end to evil and death, who frees us for eternal life. Not only that, Christ is present with us in our suffering: “And Christ through his own salvific suffering is very much present in every human suffering, and can act from within that suffering by the powers of his Spirit of truth, his consoling Spirit” (Salvifici Doloris 26).

Paul reminded the Philippians that Jesus “will transform the body of our humiliation that it may be conformed to the body of his glory” (Phil 3:21). When we see the crucified Christ, in others or in ourselves, can we also hold on to hope? Along our Lenten journey, can we fix our eyes on the crucifixion and its transformative promise of resurrection?