El punto final de todo camino humano es la muerte. Al encarar el fin de nuestro caminar en este mundo, a menudo nos preguntamos “¿Para qué sirvió mi vida?” “¿Cuál fue su significado?” “¿Hice algo bueno para mi familia, comunidad o pueblo?” A veces compartimos estas inquietudes con los que nos rodean o quizás con una persona con la que tenemos una relación de confianza. Ellos son nuestros testigos; los que nos ayudan a ver hacia atrás para discernir la calidad de los caminos que hemos tomado. La esperanza de todo ser humano es que su jornada sea interpretada con ojos de amor.

El martirio es un testimonio público del significado de la vida de una persona. Por lo general el mártir da testimonio de una vida que se opone a los valores de la sociedad, sobre todo de los que viven en el centro del poder político, social o religioso. En la Biblia, existen escenas de martirio, tanto en el antiguo como en el nuevo testamento que destacan la importancia de los que acompañan al mártir en sus últimos momentos. Estos testigos, tanto los adversarios de la persona y sus valores, como los partidarios constatan cómo el momento de la muerte concuerda con los valores vividos por la persona sufriente. En esta reflexión vamos a examinar dos escenas en las cuales las mujeres son aliadas o partidarias y toman el riesgo de estar presentes y así afirmar el valor de la vida que está al punto de extinguirse.

The endpoint of every natural human journey is death. As we face the end of our journey in this world, we often ask ourselves, "What was my life for?" “What was its meaning?” “Did I do something good for my family, community, or country?” Sometimes we share these concerns with those around us or perhaps with a person with whom we have a relationship of trust. They are our witnesses; those who help us look back to discern the quality of the paths we have taken. The hope of every human being is that their journey is interpreted with eyes of love.

Martyrdom is a public witness to the meaning of a person's life. A martyr witnesses by their life and death to a journey that opposes the values of society, especially those who live in the center of political, social, or even religious power. There are also people who surround a martyr, who witness the quality and direction of the person’s journey. In the Bible, there are scenes of martyrdom, both in the Old and New Testaments that highlight the importance of those who accompany the martyr in his or her last moments. These witnesses, both the opponents of the person and their values, as well as their supporters, confirm how the moment of death agrees with the values lived by the suffering person. In this reflection, we are going to examine two scenes in which women are allies or supporters, take the risk of being present and thus affirming the value of life that is about to be extinguished.

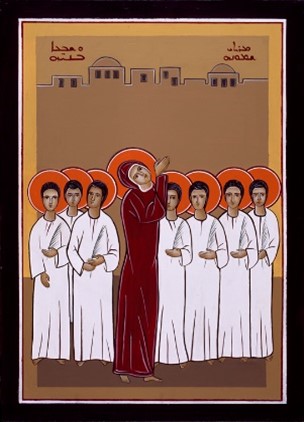

El segundo libro de los Macabeos (escrito aproximadamente 160 años antes del nacimiento de Jesús) presenta la muerte de siete hermanos mártires que viven en la época helenística en la que los conquistadores y gobernadores griegos trataban de imponer la cultura griega a los judíos. Los siete hermanos son torturados hasta la muerte porque no aceptan comer cerdo, un alimento impuro, prohibido por la Ley. El no comer el alimento prohibido es una acción de fidelidad hacia Dios. Pero también encierra una esperanza—la recompensa de Dios es la vida más allá de este momento de sufrimiento. El cuarto hijo le dice al rey que lo maltrata: “Más vale morir a manos de los hombres y aguardar las promesas de Dios que nos resucitará; tú, en cambio, no tendrás parte en la resurrección para la vida." (2 Mac 7:14). El rey, un testigo antagonista, no es conmovido por la fe de los hermanos.

La madre de los hermanos mártires es la aliada más tenaz de ellos. Ella está presente durante el suplicio de sus hijos y juega un papel activo. El narrador nos dice que:

"Por encima de todo se debe admirar y recordar a la madre de ellos, que vio morir a sus siete hijos en el espacio de un día. Lo soportó, sin embargo, e incluso con alegría, por la esperanza que ponía en el Señor. Llena de nobles sentimientos, animaba a cada uno de ellos en el idioma de sus padres. Estimulando con ardor varonil sus reflexiones de mujer," 2 Mac 7: 21-22

En esta época, el valor de esta mujer se expresa como “ardor varonil” porque en la cultura helenística, solamente los varones eran capaces de ser valientes. Sin embargo, siendo madre y mujer, ella anima a sus hijos para que den testimonio de su relación con Dios hasta la muerte. Su valentía no viene de un valor social, ni una percepción cultural, sino de la esperanza que tiene en Dios. Ella le recalca a su sexto hijo que el martirio es una apertura hacia la vida:

"No me explico cómo nacieron de mí; no fui yo la que les dio el aliento y la vida; no fui yo la que les ordenó los elementos de su cuerpo. Por eso, el Creador del mundo, que formó al hombre en el comienzo y dispuso las propiedades de cada naturaleza, les devolverá en su misericordia el aliento y la vida, ya que ustedes los desprecian ahora por amor a sus leyes." 2 Mac 7: 22-23.

La madre también muere a manos del tirano después de sus hijos varones. Esta familia anónima deja un testimonio de su fidelidad a Dios, y en esta fidelidad se basa la esperanza de la resurrección.

The second book of Maccabees (written approximately 160 years before the birth of Jesus) tells the story of the death of seven brothers who live in the Hellenistic era when the Greek conquerors and rulers were trying to impose Greek culture on the Jews. The seven brothers are tortured to death because they refuse to eat pork; an impure food, prohibited by the Law. Not eating is an act of fidelity towards God, but it also holds hope—God's reward is life beyond this moment of suffering. The fourth son tells the king who mistreats him: “It is my choice to die at the hands of mortals with the hope that God will restore me to life; but for you, there will be no resurrection to life.” (2 Mac 7: 14)

The mother of the martyred brothers is their most tenacious ally. She is present during the ordeal of her children and plays an active role. The narrator tells us that

Most admirable and worthy of everlasting remembrance was the mother who, seeing her seven sons perish in a single day, bore it courageously because of her hope in the Lord. Filled with a noble spirit that stirred her womanly reason with manly emotion, she exhorted each of them in the language of their ancestors… (2 Mac 7: 21)

At this time, the value of this woman is expressed as "manly ardor" because, in the Hellenistic culture, only men were capable of being brave. However, being a mother and a woman, she encourages her children to bear witness to their relationship with God until death. His courage does not come from a social value, nor a cultural perception, but from the hope, she has in God. She reiterates to her sixth son that martyrdom is an opening to life:

“I do not know how you came to be in my womb; it was not I who gave you breath and life, nor was it I who arranged the elements you are made of. Therefore, since it is the Creator of the universe who shaped the beginning of humankind and brought about the origin of everything, he, in his mercy, will give you back both breath and life, because you now disregard yourselves for the sake of his law.” (2 Mac 7: 22-23)

The mother also dies at the hands of the king after her sons. This anonymous family leaves a witness of their fidelity to God, and on this faithfulness is based the hope of the resurrection.

El caminar de Jesús es una vivencia del amor de Dios desde su concepción hasta su resurrección. Durante la jornada de su martirio también están presente testigos que lo acompañan; testigos antagonistas, los fariseos, sacerdotes y la gente que pasaba en camino hacia Jerusalén. Pero también están presentes sus aliadas, las mujeres que lo sirvieron durante su ministerio público. También los soldados romanos, impresionados por la manera en que muere Jesús, constatan su verdadera identidad: "El capitán y los soldados que custodiaban a Jesús, al ver el temblor y todo lo que estaba pasando, se llenaron de terror y decían: «Verdaderamente este hombre era Hijo de Dios." (Mat. 27:54)

Los enemigos de Jesús también fueron testigos de su muerte, pero no lo vieron con ojos de amor. Mas bien tomaron el amor y la esperanza que él encarnaba para convertirla en burla:

Los jefes de los sacerdotes, los jefes de los judíos y los maestros de la Ley también se burlaban de él. Decían: “¡Ha salvado a otros y no es capaz de salvarse a sí mismo! ¡Que baje de la cruz el Rey de Israel y creeremos en él! Ha puesto su confianza en Dios. Si Dios lo ama, que lo salve, pues él mismo dijo: Soy hijo de Dios.” Mateo 27: 41-43.

Los adversarios de Jesús atacan su identidad y su relación con Dios. Incluso, según el evangelio de Lucas, uno de los bandidos crucificado con él también lo insultaba: "¿No eres tú el Mesías? ¡Sálvate a ti mismo y también a nosotros." (Luc. 23:39)

Los evangelistas nos dicen que al final de la vida de Jesús, los testigos partidarios de su martirio fueron las mujeres que lo acompañaban, uno de los bandidos que crucificaron con él y los soldados romanos. Un grupo de mujeres, y una multitud le acompañaron en el camino al Gólgota (Luc 23: 27-28). Ellos lamentaban su condena, pero Jesús desvía su duelo, enfatizando el duelo que vendría con la destrucción de Jerusalén.

Pero hay un grupo de mujeres que tienen una relación más estrecha con Jesús. Los evangelios de Marcos y Mateo representan a estas mujeres, María Magdalena, María, madre de Santiago y de José, y la madre de los hijos de Zebedeo. Al llegar y ser crucificado Jesús, el evangelio de San Juan nos acerca al pie de la cruz, donde se encuentran la madre de Jesús, sus amigas y el discípulo amado. En este momento, es Jesús quien mira con ojos de amor a su madre, entregándosela a su discípulo para que la cuidara. Las mujeres, quienes habían servido a Jesús de una manera concreta y activa en su ministerio, en la crucifixión, según Marcos, Mateo y Lucas se mantienen a cierta distancia, observando lo que ocurría, hasta que lo pusieron en la tumba. Podemos imaginar que ellas veían el valor de su vida y la de su sufrimiento con ojos de amor. Cuando regresan a la tumba para ungir su cuerpo, un acto de amor y misericordia, su duelo se convierte júbilo cuando son testigos de la resurrección.

El punto final de toda vocación personal en este mundo es la muerte. Al encarnarse, al asumir la naturaleza humana desde la concepción hasta la muerte Jesús vivió estos dos grandes momentos de transición en la vida de las personas. Pero, su amor encarnado también nos dice que el fin de la jornada puede vislumbrarse en la resurrección.

Jesus' journey is an experience of God's love from his conception to his resurrection. During his martyrdom, he is accompanied by many people: antagonistic witnesses, such as the Pharisees, priests, and people who passed by his Cross on their way to Jerusalem. But his allies are also present, the women who served him during his public ministry. Also, Roman soldiers, impressed by the way in which Jesus dies, confirm his true identity: “The centurion and the men with him who were keeping watch over Jesus feared greatly when they saw the earthquake and all that was happening, and they said, “Truly, this was the Son of God!” (Matt. 27:54)

The enemies of Jesus also witnessed his death, but they did not see him with eyes of love. Rather they took the love and hope that he embodied to turn it into a mockery:

Likewise, the chief priests with the scribes and elders mocked him and said, “He saved others; he cannot save himself. So, he is the king of Israel! Let him come down from the cross now, and we will believe in him. He trusted in God; let him deliver him now if he wants him. For he said, ‘I am the Son of God.’” (Matt. 27: 41-43)

Jesus' adversaries attack his identity and his relationship with God. According to the Gospel of Luke, one of the criminals crucified with him also insulted him: “Are you not the Messiah? Save yourself and us.” (Luke 23:39)

The gospels tell us that at the end of Jesus' life, the supportive witnesses to his martyrdom were the women who accompanied him, one of the bandits who crucified with him, and the Roman soldiers. A group of women and a crowd accompanied him on the way to Golgotha (Luke 23: 27-28). They mourned his condemnation; but Jesus diverted their mourning, emphasizing the distress that would come with the destruction of Jerusalem.

Nevertheless, there is a group of women who have an even closer relationship with Jesus. The Gospels of Mark and Matthew these women, Mary Magdalene, Mary, mother of James and Joseph, and the mother of Zebedee's children. When Jesus arrives and is crucified, the Gospel of Saint John brings us closer to the foot of the cross, where the mother of Jesus, her friends and the beloved disciple are. At this moment, it is Jesus who looks with eyes of love at his mother, handing her over to his disciple to take care of her. The women, who had served Jesus in a concrete and active way in his ministry, at the crucifixion, according to Mark, Matthew and Luke, kept a certain distance, observing what was happening until they put him in the tomb. We can imagine that they saw the value of his life and that of his suffering with eyes of love. When they return to the tomb to anoint his body, an act of love and mercy, their mourning turns to joy as they witness his resurrection.

The endpoint of every personal vocation in this world is death. By becoming incarnate, by assuming human nature from conception to death, Jesus experienced these two great moments of transition in people's lives. But, his incarnate love also tells us that the real end of the journey, the end of a personal vocation, can be glimpsed in the resurrection.

La Madre en Macabeos no tiene nombre; pero su testimonio es tan poderoso que la tradición siríaca (las iglesias del oriente, incluyendo la maronita en el Líbano) le dio el nombre Shmouni y es venerada el primero de Agosto. Ella mira con ojos de fidelidad y esperanza el suplicio de sus hijos. En la crucifixión de Jesús, la presencia de la madre de Jesús, de las mujeres que tienen nombre y las que no, y el discípulo amado son los testigos con ojos de amor de su jornada.

¿Cómo presenciamos hoy la jornada de Jesús? Nuestras devociones y oraciones—el Via crucis, la devoción a la Virgen de los Dolores, la oración Anima Cristi, nos colocan en el momento final de la vida natural de Jesús, pero este es un portal hacia la resurrección. El martirio de personas no ha cesado. En nuestro mundo también son testigos del amor de Dios y la esperanza más allá del sufrimiento. Es por lo que un mártir puede decir:

“Si me matan resucitaré en el pueblo salvadoreño.” Monseñor Oscar Romero.

The mother in Maccabees has no name; but her testimony is so powerful that the Syriac tradition (the churches of the East, including the Maronite in Lebanon) gave her the name Shmouni and she is venerated on the first of August. She looks with eyes of fidelity and hope at the ordeal of her children. In the crucifixion of Jesus, the presence of the mother of Jesus, of the women who have names, those who do not, and the beloved disciple are the loving eyewitnesses to his entire journey.

How do we witness to Jesus’s journey today? Our devotions and prayers—the Stations of the Cross, the devotion to Our Lady of Sorrows, the Anima Christi prayer—place us at the final moment of Jesus' natural life, but they are the doorway to the resurrection. Even today, however, the martyrdom of people in our present world are witnesses to God's love and hope beyond suffering. That is why a martyr can say:

“If they kill me, I will resurrect in the Salvadoran people.” Monsignor Oscar Romero.