Durante las charlas de la semana pasada, la Dra. Gray nos guió a través del proceso en que el apóstol Pablo reconoció a Cristo crucificado en la vida de las comunidades a las que escribió. Ella reflexionó sobre las preguntas:

También miramos las maneras en que Jesús fue acompañado por testigos cuya presencia constata el significado de su vida, muerte y resurrección. Meditamos sobre la idea de que, como Jesús, enfrentamos el final de nuestro caminar en este mundo, y por lo que a menudo nos preguntamos:

Hoy enfocamos a la manera en que un caminar o un llamado de Dios puede cambiar o adaptarse al terreno de la experiencia vivida

During last week’s talks, Dr. Gray led us through the way the Apostle Paul recognized the crucified Christ in the life of the communities he wrote to. She reflected on the questions:

We also looked at the ways in which Jesus was accompanied by witnesses whose presence testified to the meaning of his life, death, and resurrection. We meditated on the idea that like Jesus, we face the end of our journey in this world, so we often ask ourselves,

Today we shift our focus to the way a journey or calling from God may shift or adapt to the terrain of lived experience.

Cuando se nos llama a emprender un viaje, solemos responder positivamente, sobre todo si nos invita a progresar de lo bueno, a lo mejor, a lo superior. En otras palabras, nos mueve hacia adelante la felicidad, la alegría o la bondad. Sin embargo, cuando el camino implica sufrimiento para avanzar hacia la felicidad, la alegría o el bien, naturalmente dudamos, a veces incluso podemos dudar del significado del viaje en sí. A menudo, lo que nos ayuda en nuestra toma de decisiones es tener amigos que revisen el camino de nuestra vida; para discernir cómo este es el llamado de Dios, y para comprender el siguiente paso.

When we are called on a journey, we usually respond positively if it seems to invite us to go from good to better to best. In other words, we are called forward by happiness, joy, or goodness. However, when the journey involves suffering to move toward happiness, joy, or goodness, we naturally hesitate, sometimes we may even doubt the meaning of the journey itself. Often what helps in our decision-making is to have friends to look over our life’s journey; to discern how this is God’s call for our lives, to understand the next step.

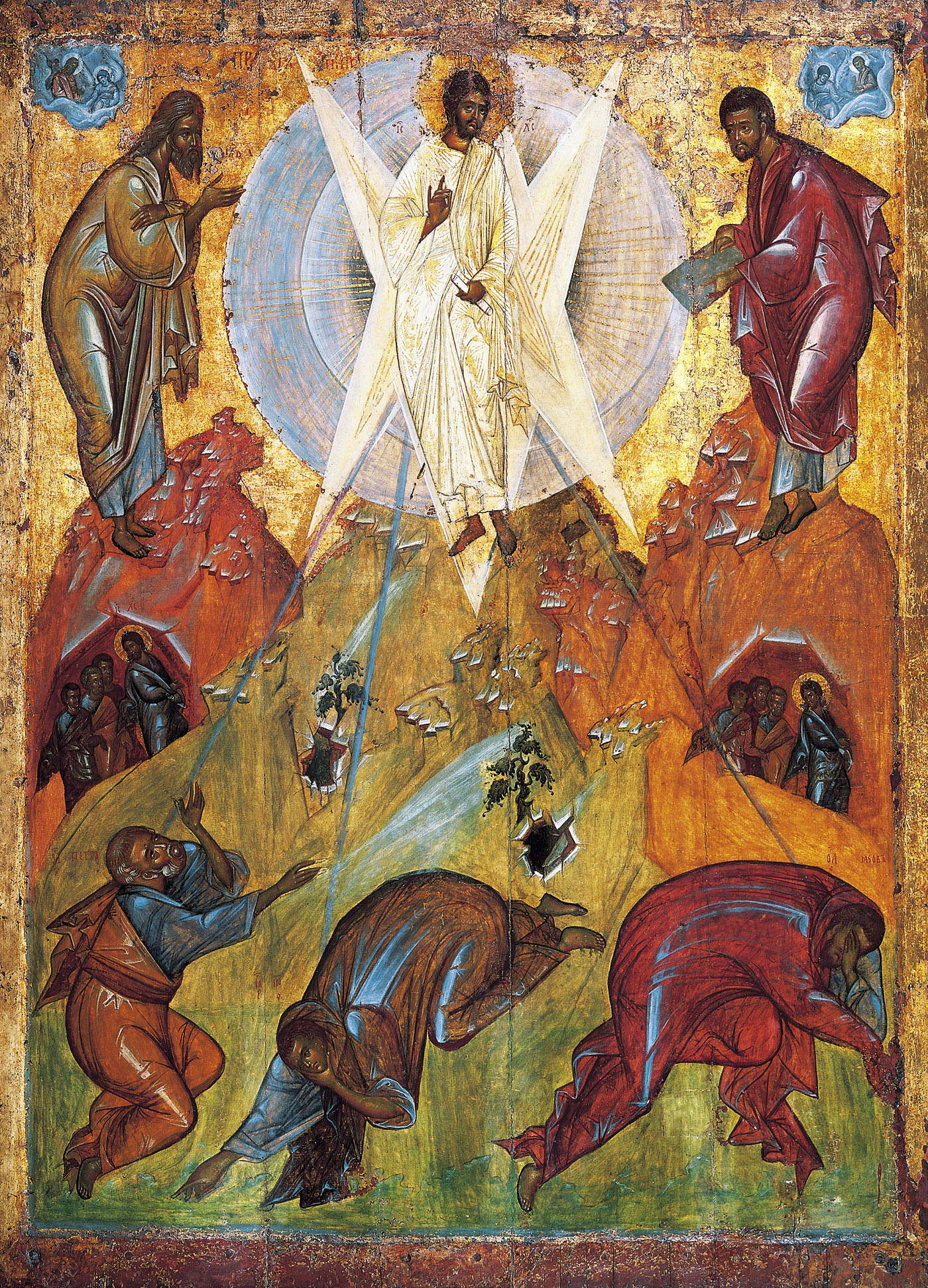

Hace unas semanas, la lectura del evangelio de Lucas presenta la Transfiguración, un momento en el que Jesús habla a los testigos celestiales sobre los hechos de su pasión, que pronto estarían ocurriendo.

“Unos ocho días después de estos discursos, Jesús tomó consigo a Pedro, a Santiago y a Juan y subió a un cerro a orar. Y mientras estaba orando, su cara cambió de aspecto y su ropa se volvió de una blancura fulgurante. Dos hombres, que eran Moisés y Elías, conversaban con él. Se veían en un estado de gloria y hablaban de su partida (éxodo), que debía cumplirse en Jerusalén.” (Lucas 9: 28-32)

La palabra exodón aparece en la versión griega de este texto, y aunque puede traducirse como “partida” o incluso “muerte” la palabra es éxodo. Éxodo en este contexto también se refiera a la gran historia de la redención de la esclavitud en la Biblia hebrea/Antiguo Testamento. Susan Garett, estudiosa del Nuevo Testamento dice:

La memoria colectiva del éxodo de Egipto dio forma a los relatos de los actos de redención de Dios en el pasado y proporcionó la expresión arquetípica de toda esperanza futura. Por lo tanto, era apropiado que Lucas sugiriera que, durante la transfiguración, Jesús había discutido con Moisés y Elías “su éxodo (έξοδος), que estaba a punto de realizar en Jerusalén” (Lucas 9:31). Lucas insinúa con ello que la redención que [realizará] Jesús a través de la muerte, la resurrección y la ascensión recordará de alguna manera la redención de Israel de Egipto, de la casa de la servidumbre.1

Podríamos imaginar a Jesús y a Moisés, el gran líder del Éxodo, dialogando sobre asuntos como “¿Cómo fue para ti?" “¿Estabas asustado?” pero lo que es más importante, serian preguntas como: “¿Cómo te mantuviste enfocado?” “¿Cuándo supiste que tenías que hacer cambios?” Quizás Moisés dijo: “Elías aquí con nosotros, él está aquí porque su presencia anuncia el hecho de que tú eres en verdad el Mesías.” El evangelio de Lucas no transmite el contenido de este intercambio, pero si dice que Jesús dialogó con ellos.

In the gospel reading from a few weeks ago, Luke’s gospel presents the Transfiguration, a moment when Jesus talks to heavenly witnesses about the events of his passion, that would soon be taking place.

About eight days after he said this, he took Peter, John, and James and went up the mountain to pray. While he was praying his face changed in appearance and his clothing became dazzling white. And behold, two men were conversing with him, Moses and Elijah, who appeared in glory and spoke of his exodus that he was going to accomplish in Jerusalem. (Lk 9:28b-36)

The word exodon appears in the Greek version of this text, and although it can be translated as “departure,” or even “death,” the New American Bible preserves the word exodus. The reason is that it references the great story of redemption from slavery in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. Susan Garett, a New Testament scholar:

The collective memory of the exodus from Egypt shaped accounts of God’s past acts of redemption and provided the archetypal expression for all future hope. Thus, it was appropriate for Luke to suggest that, during the transfiguration, Jesus had discussed with Moses and Elijah “his exodus (έξοδος), which he was about to accomplish in Jerusalem” (Luke 9:31). Luke hints thereby that the redemption to be [worked] by Jesus through the death, resurrection, and ascension will in some way recall Israel’s redemption out of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.1

We could imagine Jesus and Moses, the great leader of the Exodus, dialoguing about things like “What was it like for you?” “Were you frightened?” but more importantly, questions such as: “How did you stay focused?” “When did you know you had to make changes?” Perhaps Moses may have said, “Elijah standing here with us, he is here because his presence announces the fact that you are indeed the Messiah.” Luke’s gospel does not relay the content of their exchange, but it does say that Jesus dialogued with them.

1 Susan R. Garrett, “Exodus from Bondage: Luke 9:31 and Acts 12:1-24” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 52, 1990, 656.

Mientras Moisés, Elías y Jesús conversan, es posible que hayan aprovechado su memoria colectiva, la memoria de su pueblo sobre el éxodo de Egipto, y la forma en que recuerda los actos pasados de redención de Dios y la esperanza futura. Un tema central de la experiencia del Éxodo es que Dios escucha el clamor de su pueblo y decide liberarlo de la opresión de sus amos:

“Yavé dijo: «He visto la humillación de mi pueblo en Egipto, y he escuchado sus gritos cuando lo maltrataban sus capataces. Yo conozco sus sufrimientos, y por esta razón estoy bajando, para librarlo del poder de los egipcios y para hacerlo subir de aquí a un país grande y fértil, a una tierra que mana leche” (Exodo 3: 7-8)

Estas palabras bien podrían adaptarse para describir el éxodo de Jesús:

He sido testigo de la aflicción de mi pueblo en todo el mundo y he oído su clamor contra sus capataces, por lo que sé bien lo que están sufriendo. Por lo tanto, he descendido para rescatarlos de los poderes que los oprimen y sacarlos de ese lugar hacia una tierra donde puedan ser libres para adorarme.

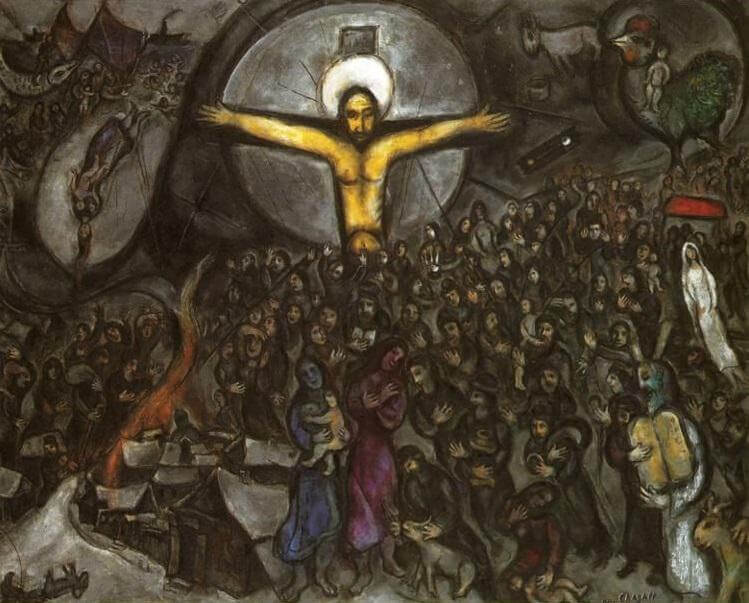

Marc Chagall, un artista judío que trabajó antes, durante y después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, a menudo pintaba al Cristo crucificado en diferentes escenarios. Sin embargo, en la década de los cincuentas, después de que se conociera la verdadera naturaleza del holocausto, “Chagall presenta, no a Moisés, sino a Jesús en la cruz como la figura central del Éxodo. Jesús lleva un halo como salvador del pueblo elegido, posiblemente un testimonio del hecho de que al menos algunos judíos sobrevivieron al plan de exterminio nazi”.2 La imagen de Chagall de Jesús en la experiencia del éxodo representa las muchas formas de opresión y las muchas personas que lo viven. Su pintura revela figuras de madres, niños, novias, hombres, animales e incluso Moisés que lleva las tablas de los mandamientos. Sobre todos ellos, Cristo crucificado extiende sus brazos protectores.

La opresión tiene muchas caras y lugares, pero Éxodo también nos asegura de la empatía y la acción de Dios. Dios le dice a Moisés: “Yo soy el Señor. Los libraré de las cargas de los egipcios y los libraré de su servidumbre. Los redimiré con mi brazo extendido y con poderosos juicios” (Éxodo 6:6) El libro de Deuteronomio también usa esta imagen para hablar del Éxodo: “Acuérdate que tú también fuiste un día esclavo en la tierra de Egipto, y el Señor tu Dios te sacó de allí con mano fuerte y brazo extendido.” (Deut. 5:15) La mano fuerte y el brazo extendido simbolizan dos aspectos del poder salvador de Dios:

En el evento del Éxodo, no se trata meramente de un Dios... que causa destrucción en Egipto, golpeándo a su rey... se trata también de un Dios que bendice, protege y cuida a Israel... El brazo que fue extendido en la creación según el profeta Jeremías es el mismo que salvó, bendijo y creó a Israel en el Éxodo.3

El poder de Dios para herir, pero también para crear, y ser misericordioso combinados es una parte importante de la memoria colectiva de Israel; es este el recuerdo que Jesús, Moisés y Elías pueden haber compartido en su conversación.

As Moses, Elijah, and Jesus converse, they may have tapped into their collective memory; their people’s memory of the exodus from Egypt, and the way it recalls God’s past acts of redemption and future hope. A central theme of the Exodus experience is that God hears the cries of his people and decides to free them from the oppression of their slave masters:

…The LORD said: I have witnessed the affliction of my people in Egypt and have heard their cry against their taskmasters, so I know well what they are suffering. Therefore I have come down to rescue them from the power of the Egyptians and lead them up from that land into a good and spacious land… (Exodus 3:7-8)

These words could very well be adapted to describe Jesus’ journey:

I have witnessed the affliction of my people all over the world and heard their cry against their taskmasters, so I know well what they are suffering. Therefore, I have come down to rescue them from the powers that oppress them and lead them up from that place into a land where they can be free to worship me.

Marc Chagall, a Jewish painter who worked before, during, and after WWII, often painted the crucified Christ in different settings. However, in the 1950s, after the true nature of the holocaust became known, “Chagall presents, not Moses, but Jesus on the cross as the central figure of the Exodus. Jesus wears a halo as savior of the chosen people, possibly a testament to the fact that at least some Jews survived the Nazi extermination plan.”2 Chagall’s image of Jesus in the exodus experience speaks to the many forms of oppression in our time, and to people in many circumstances. A close look at his painting reveals figures of mothers, children, brides, men, animals, and even Moses carrying the tablets of the commandments. Over all of these, the crucified Christ stretches out his protective arms.

Oppression has many faces and locations, but Exodus also assures us of God’s concern and involvement. God tells Moses: “I am the LORD. I will free you from the burdens of the Egyptians and will deliver you from their slavery. I will redeem you by my outstretched arm and with mighty acts of judgment.” (Exodus 6:6) The Book of Deuteronomy also uses this image to speak of the Exodus: “Remember that you too were once slaves in the land of Egypt, and the LORD, your God, brought you out from there with a strong hand and outstretched arm.” (Deut. 5:15) The strong arm and outstretched arm symbolize two aspects of God’s saving power:

In the Exodus event, it is not simply or merely a matter of a God…who wreaks destruction on Egypt, bashing it and its king…but it is also equally a matter of a God who blesses, protects, and cares for Israel…The arm that was outstretched in creation according to the prophet Jeremiah is the very same one that saved, blessed, and created Israel in the Exodus.3

God’s power to smite, but also to create, and be merciful combined is an important part of the collective memory of Israel; the memory that Jesus, Moses and Elijah may have shared in their conversation.

2 Karen Sue Smith, “Child, Martyr, Everyman: Chagall’s Jewish Jesus,” America: The Jesuit Review, March 3 2014.

3 Brent M. Strawn, “‘With a Strong Hand and Outstretched Arm’: On the Meanings of the Exodus Tradition,” in Iconographic Exegesis of the Hebrew Bible/ Old Testament: An Introduction to Its Method and Practice, edited by Izaak J. De Hulster, Brent A. Strawn and Ryan P. Bonfiglio, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht (2005), 115.

La libertad de la opresión puede significar ser liberados de la esclavitud económica o física, y la opresión religiosa. Todas estas condiciones están representadas en la historia del Éxodo. Sin embargo, también existe una liberaciٴón importante que es esencial para la vida: el ser libre de la mentalidad de esclavo. Los israelitas quedan atrapados en la red de la mente de esclavo antes y después de la experiencia del éxodo:

Moisés les dijo esto [el llamado de Dios a la libertad] a los israelitas; pero no quisieron escuchar a Moisés, a causa de su espíritu quebrantado y su cruel esclavitud. (Éxodo 6:9)

Habiendo partido de Elim, toda la comunidad de Israel llegó al desierto de Sin, que está entre Elim y Sinaí, el día quince del segundo mes después de su salida de la tierra de Egipto. Aquí en el desierto, toda la comunidad de Israel se quejó contra Moisés y Aarón. Los israelitas les dijeron: “¡Ojalá hubiéramos muerto por la mano del Señor en la tierra de Egipto, cuando nos sentábamos junto a nuestras ollas de carne y comíamos hasta saciarnos de pan! ¡Pero tú nos has conducido a este desierto para que toda esta asamblea muera de hambre! (Éxodo 16: 1-3)

En última instancia, Moisés se ve obligado a cambiar su camino, de modo que el pueblo de Israel divaga por el desierto durante 40 años hasta que se purga esta manera de pensar.

Freedom from oppression can mean freedom from economic bondage, physical bondage and religious oppression. All of these are represented in the Exodus story. However, there is also important freedom that is essential to be able to move forward into life: to be free from the mindset of slavery. The Israelites are caught in its web both before and after the exodus experience:

Moses told this [God’s call to freedom] to the Israelites; but they would not listen to Moses, because of their broken spirit and their cruel slavery. (Exodus 6:9)

Having set out from Elim, the whole Israelite community came into the wilderness of Sin, which is between Elim and Sinai, on the fifteenth day of the second month after their departure from the land of Egypt. 2 Here in the wilderness the whole Israelite community grumbled against Moses and Aaron. 3 The Israelites said to them, “If only we had died at the LORD’s hand in the land of Egypt, as we sat by our kettles of meat and ate our fill of bread! But you have led us into this wilderness to make this whole assembly die of famine!” (Exodus 16: 1-3)

Ultimately, Moses is forced to change their journey, so that they wander in the desert for 40 years until this mindset is purged.

Además de Moisés y Elías, estuvieron presentes otros testigos en la Transfiguración. El evangelio de Lucas nos dice que Pedro, Juan y Santiago estaban presentes, orando con él. Quedaron deslumbrados por lo que presenciaron y abrumados por la voz que decía: “Este es mi Hijo, escúchenlo. Después que la voz habló, Jesús estaba solo. Se callaron y en ese momento no dijeron a nadie lo que habían visto.” (Lucas 9:35-6) Los testigos terrenales de Jesús, sus discípulos, quedan desconcertados y asustados por esta experiencia. ¿Nos pasa también a nosotros? ¿Nos asusta la magnitud del camino?

At the Transfiguration, other witnesses were present in addition to Moses and Elijah. Luke’s gospel tells us that Peter, John, and James were present, praying with him. They were bedazzled by what they witnessed and overwhelmed by the voice saying: “This is my Son, listen to him. After the voice had spoken, Jesus was found alone. They fell silent and did not at that time tell anyone what they had seen.” (Luke 9:35-6) Jesus’ earthly witnesses, the disciples, are puzzled and frightened by this experience. Does this also happen to us? Does the magnitude of the journey frighten us?