Traducción de Gerardo Yvan Morales

Nuestra tradición nos enseña que lo que se revela acerca de Cristo en el Nuevo Testamento también se puede encontrar oculto en el Antiguo Testamento. Jesús hace cumplir las escrituras. Necesitamos estudiar lo Antiguo para comprender lo Nuevo. Creo que también estudiamos lo Antiguo para entendernos a nosotros mismos. A veces Cristo es tan único que es difícil para nosotros relacionarnos con Cristo. El Antiguo Testamento nos da historias de personas un poco como Cristo y un poco como nosotros. Ahí es donde Abrahán nos ayuda. Abrahán es un ejemplo de fe y un amigo de Dios, pero también un poco quebrantado a veces. Esta noche quiero comparar la Vía Dolorosa de Cristo con la jornada de Abrahán. Creo que si comparamos a Abrahán y Cristo entenderemos un poco mejor su sufrimiento. En última instancia, creo que podemos encontrar significado en nuestras propias penas y en las penas de nuestro prójimo si entendemos cómo las penas a veces funcionan en los planes de Dios.

Cuando yo era niño, lo llamábamos las estaciones de la cruz. Cuando viví en Jerusalén la llamábamos la Vía Dolorosa. Esta noche la voy a llamar la Vía Dolorosa, principalmente porque todos tenemos dolor en nuestros caminos. Sólo en sentido figurado llevamos todos nuestra cruz. Voy a estar hablando de las figuras de Cristo lo suficiente como para no necesitar agregar más palabras figurativas. Conectaré las catorce estaciones con la historia de Abrahán, pero siguiendo el orden de la vida de Abrahán, no el orden de las estaciones. Si planea caminar por las estaciones mientras hablo, espero que tenga un rastreador de actividad física. Obtendrá muchos pasos.

Our tradition teaches us that what is revealed about Christ in the New Testament can also be found hidden in the Old Testament. Jesus fulfills the scriptures. We need to study the Old in order to understand the New. I think that we also study the Old to understand ourselves. Sometimes Christ is so unique that it is hard for us to relate to Christ. The Old Testament gives us stories of people a bit like Christ and a bit like ourselves. That is where Abraham helps us. Abraham is an example of faith and a friend of God, but also a bit broken at times. Tonight I want to compare the Via Dolorosa of Christ to the journey of Abraham. I think if we compare Abraham and Christ we will understand their suffering a little better. Ultimately, I think we can encounter meaning in our own sorrows and the sorrows of our neighbors if we understand how sorrows sometimes work in God’s plans.

When I was growing up we called it the stations of the cross. When I lived in Jerusalem we called it the Via Dolorosa, the sorrowful way. Tonight I’m going to call it the Via Dolorosa, mainly because we all have sorrows on our way. Only figuratively do we all bear a cross. I’m going to be talking about figures of Christ enough that I don’t need to add more figurative words. I will connect all fourteen stations to the story of Abraham, but following the order of the life of Abraham, not the order of the stations. If you’re planning to walk the stations while I talk, I hope you have a fitness tracker. You will get lots of steps in.

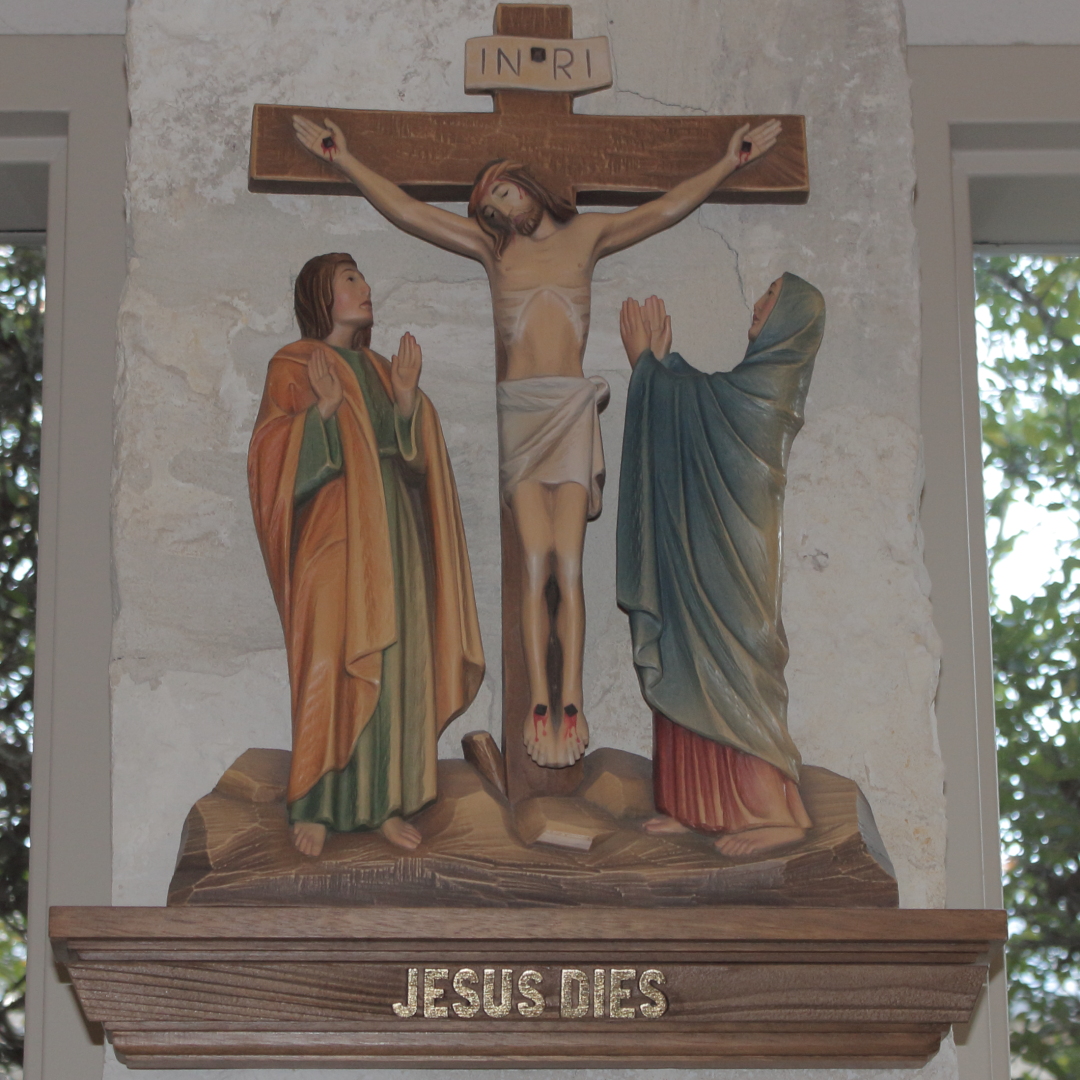

La historia de Abrahán comienza en el capítulo doce de Génesis, y voy a comenzar la vía en la estación doce. Jesús muere. ¿Qué significa morir? ¿Cómo me sentí cuando murió mi abuela? Se sentía como si se estuviera alejando del resto de nosotros. Creí que ella tenía más bendiciones por delante, pero aun así fue doloroso. El viaje a la muerte fue doloroso, su muerte fue dolorosa y el viaje por delante fue incierto. Cuando comienza la historia de Abrahán, creo que primero la escuchamos como gloriosa, un momento milagroso de gracia y elección. Escuchemos de nuevo las penas que debieron sentir Abrahán y su familia.

El Señor dijo a Abram: «Deja tu tierra natal y la casa de tu padre, y ve al país que yo te mostraré. Yo haré de ti una gran nación y te bendeciré; engrandeceré tu nombre y serás una bendición. Bendeciré a los que te bendigan y maldeciré al que te maldiga, y por ti se bendecirán todos los pueblos de la tierra». Abram partió, como el Señor se lo había ordenado, y Lot se fue con él. Cuando salió de Jarán, Abram tenía setenta y cinco años. (Génesis 12:1-4 LPD)

La partida de Abrahán se debe haber sentido como la muerte para su familia. Creer en el propósito de Dios para Abrahán, para la muerte de Jesús, para la muerte de la abuela es doloroso, pero significativo. El eufemismo hebreo para morir es “ser reunido con tu pueblo”, de modo que cuando se describe la muerte de Abrahán en Génesis 25:8, suena como lo contrario de ser separado de su pueblo en Génesis 12:1. ¿Podemos aceptar que la muerte tiene tanto que ver con el regreso a casa como con la separación?

The story of Abraham starts in Genesis chapter twelve, and I’m going to start the via at station twelve. Jesus dies. What does it mean to die? How did I feel when grandma died? It felt like she was going away from the rest of us. I believed that she had more blessings ahead of her, but it was still sorrowful. The journey to death was sorrowful, her death was sorrowful, and the journey ahead was uncertain. When the story of Abraham opens, I think we first hear it as glorious, a miraculous moment of grace and chosenness. Let us listen again for the sorrows that Abraham and his family must have felt.

The LORD said to Abram: Go forth from your land, your relatives, and from your father’s house to a land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you; I will make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you and curse those who curse you. All the families of the earth will find blessing in you. Abram went as the LORD directed him, and Lot went with him. Abram was seventy-five years old when he left Haran. (Gen 12:1-4 NAB)

Abraham’s departure must of have felt like death to his family. Belief in God’s purpose for Abraham, for the death of Jesus, for the death of Grandma is sorrowful, but meaningful. The Hebrew euphemism for dying is “to be gathered to your people,” so that when Abraham’s death is described in Genesis 25:8, it sounds like the opposite of being separated from his people in Genesis 12:1. Can we accept that death is as much about gathering home as it is about separation?

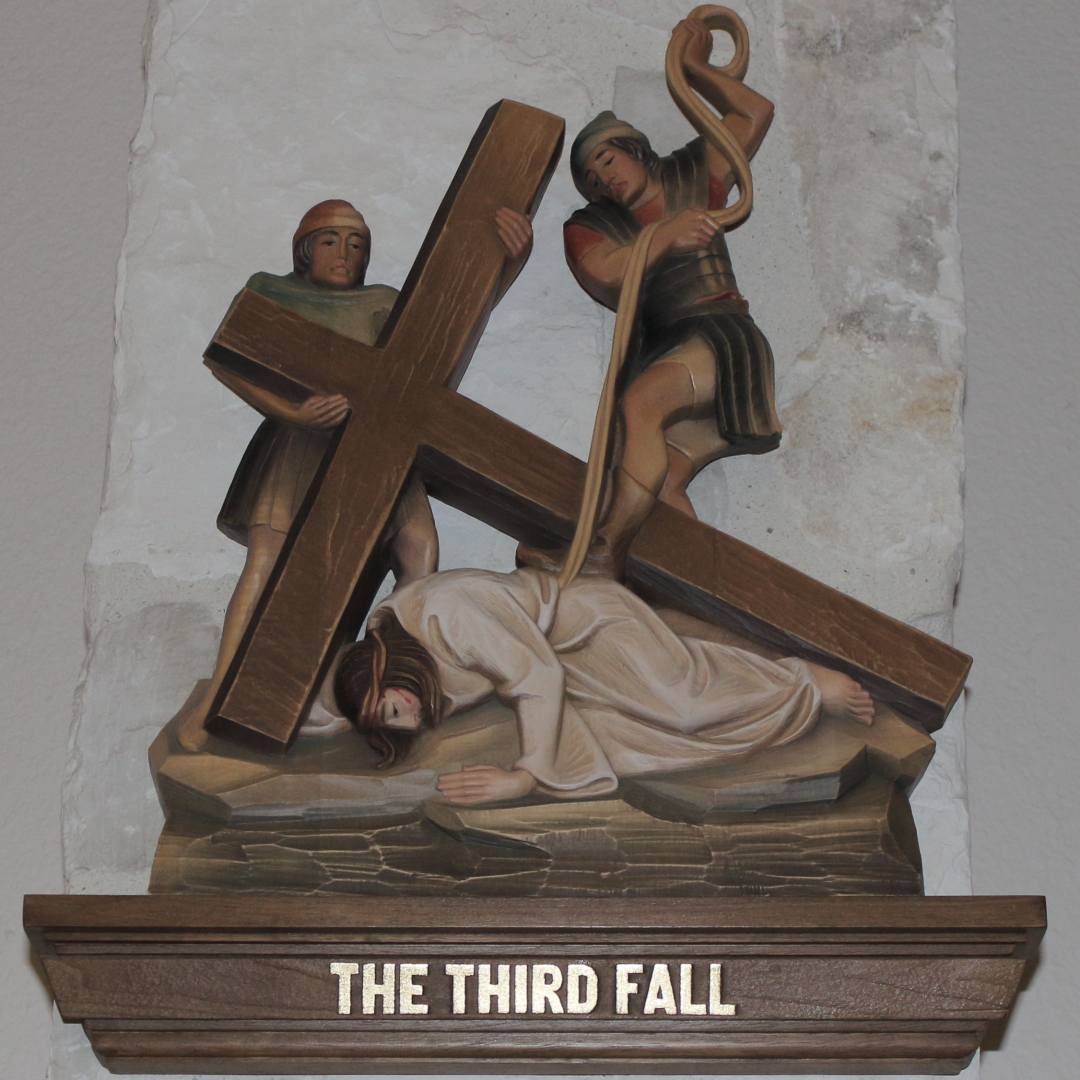

La, tercera, séptima y novena estaciones son Jesús cayendo tres veces. No sería lo mismo tener una sola estación para caer tres veces. Es la repetición más que la caída lo que es doloroso. Y eso me suena bien. Las penas que siguen ocurriendo una y otra vez son peores que una pena que vino y se fue. Abrahán también tenía este problema. Tres veces en Génesis, Abrahán o su hijo Isaac entregan a su esposa para protegerse. Cada vez, es una desgracia. Puede o no haber sido una mentira total decir que su esposa es su hermana. La desgracia es entregar a cualquier mujer al tráfico sexual.

Cuando estaba por llegar a Egipto, dijo a Sarai, su mujer: «Yo sé que eres una mujer hermosa. Por eso los egipcios, apenas te vean, dirán: «Es su mujer», y me matarán, mientras que a ti te dejarán con vida. Por favor, di que eres mi hermana. Así yo seré bien tratado en atención a ti, y gracias a ti, salvaré mi vida». (Génesis 12:11-13 LPD) (Génesis 12:11-13 LPD)

La historia nos deja preguntándonos cómo se sintió Sarah al respecto. El hecho de que Dios protegió a Sara no hace que sea mejor que Abrahán no haya aprendido su lección o se la haya enseñado a su hijo. Lo mismo vuelve a suceder en Génesis 20. Lo mismo vuelve a suceder en Génesis 26. Los estudiosos dirían que esta redundancia es el resultado del proceso de edición de las tradiciones orales. La historia tal como nos llega es una historia de dolor que se magnifica a medida que se repite y se repite. Así como nos arrepentimos de nuestros pecados durante la Cuaresma, ¿qué es más doloroso que el pecado que nunca parece alejarse por mucho tiempo?

The third, seventh, and ninth stations are Jesus falling three times. It would not be the same to have a single station for falling three times. It is the repetition more than the falling that is sorrowful. And that sounds right to me. The sorrows that keep happening over and over are worse than one sorrow that came and went. Abraham had this problem too. Three times in Genesis, Abraham or his son Isaac hands over his wife to protect himself. Each time it is a disgrace. It may or may not have been a total lie to say his wife is his sister. The disgrace is to hand any woman over to sex trafficking.

When he was about to enter Egypt, he said to his wife Sarai: “I know that you are a beautiful woman. When the Egyptians see you, they will say, ‘She is his wife’; then they will kill me, but let you live. Please say, therefore, that you are my sister, so that I may fare well on your account and my life may be spared for your sake.” (Gen 12:11-13 NAB)

The story leaves us to wonder how Sarah felt about this. The fact that God protected Sarah does not make it any better that Abraham did not learn his lesson or teach it to his son. The same thing happens again in Genesis 20. The same thing happens again in Genesis 26. Scholars would say that this redundancy is the result of the process of editing together oral traditions. The story as it comes to us is a story of sorrow that is magnified as it repeats, and repeats. As we repent of our sins during Lent, what is more sorrowful than the sin that never seems to stay away for long?

El héroe de la historia de Abrahán no es Abrahán sino Dios. Dios está a cargo de llevar a cabo las promesas de Dios. Dios hace que las cosas funcionen al final, a pesar de los peores defectos de Abrahán. Dios parece tener sentido del humor acerca de empujar a las personas a roles inesperados. Cada vez que Abrahán o Isaac sacrifican a una esposa porque temen por su propia seguridad, Dios convierte al temido malo en el bueno. Dios no solo evita que Faraón viole a Sara, Dios hace que Faraón enriquezca a Abrahán al salir. Ciertamente, este no es un ejemplo de recompensa por las buenas obras, sino un ejemplo de la gracia de Dios que viene de direcciones inesperadas. La lista de regalos es más larga en el caso de Abimelec:

Abimélec tomó ovejas y vacas, esclavos y esclavas, y se los dio a Abrahán; y también le devolvió a Sara, su esposa. Después le dijo: «Mi país está a su disposición: radícate donde mejor te parezca». Y a Sara le dijo: «He dado mil monedas de plata a tu hermano. Esto eliminará toda sospecha contra ti en aquellos que están contigo, y tú quedarás enteramente rehabilitada». (Génesis 20:14-16 LPD)

Personalmente, creo que Abrahán debería haber liberado a los esclavos y Abimelec debería haberle dado el dinero a la pobre Sara, pero nuevamente Abrahán es el centro como receptor de los dones inmerecidos de Dios. En cualquier caso, estos cambios de roles y los dones de Dios que vienen de direcciones inesperadas me recuerdan a Simón de Cirene, la quinta estación. Los Evangelios no nos dicen mucho excepto que los romanos lo obligaron, así que creo que es seguro concluir que estuvo allí por malas razones y lo ayudó en contra de su voluntad. No importa, era la voluntad de Dios que Jesús no fuera el único en llevar una cruz ese día. A veces nosotros (como Simón, Faraón y Abimelec) tenemos que llevar una cruz que no esperábamos. A veces el alivio viene de alguien a quien no considerábamos un amigo. ¿Podemos aceptar que ambos son de Dios?

The hero of the Abraham story is not Abraham but God. God is in charge of carrying out God’s promises. God makes things work out in the end, despite Abraham’s worst flaws. God seems to have a sense of humor about pushing people into unexpected roles. Each time Abraham or Isaac sacrifices a wife because he fears for his own safety, God turns the feared bad guy into the good guy. God not only prevents Pharaoh from raping Sarah, God causes Pharaoh to make Abraham wealthy on his way out. Certainly this is not an example of reward for good deeds, but an example of God’s grace coming from unexpected directions. The list of gifts is longer in the case of Abimelech:

Then Abimelech took flocks and herds and male and female slaves and gave them to Abraham; and he restored his wife Sarah to him. Then Abimelech said, “Here, my land is at your disposal; settle wherever you please.” To Sarah he said: “I hereby give your brother a thousand shekels of silver.” (Gen 20:14-16 NAB)

Personally, I think Abraham should have freed the slaves and Abimelech should have given the money to poor Sarah, but again Abraham is the focus as the recipient of God’s unmerited gifts. At any rate, these role reversals and God’s gifts coming from unexpected directions remind me of Simon of Cyrene, the fifth station. The Gospels don’t tell us much except that the Romans compelled him, so I think it is safe to conclude that he was there for bad reasons and helped against his will. No matter, it was God’s will that Jesus not be the only one to carry a cross that day. Sometimes we (like Simon, Pharaoh, and Abimelech) have to carry a cross we were not expecting. Sometimes relief comes from someone we did not consider a friend. Can we accept that both are from God?

A veces un regalo surge de un encuentro doloroso. Eso es lo que sucede cuando Verónica limpia el rostro de Jesús. Jesús la deja con su imagen. ¿Qué manera de recordar a Jesús? Abrahán tiene un extraño encuentro con un sacerdote llamado Melquisedec. Al igual que con Jesús, llega en un momento de dolor. Abrahán enfrenta un conflicto armado para proteger a su familia. El encuentro es tan misterioso como el encuentro con Verónica.

Y Melquisedec, rey de Salem, que era sacerdote de Dios, el Altísimo, hizo traer pan y vino, y bendijo a Abram, diciendo: «¡Bendito sea Abram de parte de Dios, el Altísimo, creador del cielo y de la tierra! ¡Bendito sea Dios, el Altísimo, que entregó a tus enemigos en tus manos!». (Génesis 14:18-20 LPD)

El sacerdocio del Dios de Abrahán no se establecería oficialmente hasta varios cientos de años más en los días de Moisés y Aarón. Lo que es aún más misterioso es la ofrenda sacerdotal de pan y vino, que no era una ofrenda común en ese tiempo. Esta imagen nos es familiar en nuestro recuerdo de Jesús, la Eucaristía, que fue instituida en un futuro lejano para Abrahán. En un caso, Verónica recibió un recuerdo de Jesús en la imagen del paño que usó para limpiar el rostro de Jesús, En el otro caso, Abrahán recibió un recuerdo de Jesús en la sustancia de la Eucaristía. Parece que es importante para Jesús que lo recordemos.

Sometimes a gift comes out of an encounter in sorrow. That’s what happens when Veronica wipes the face of Jesus. Jesus leaves her with his image. What a way to remember Jesus? Abraham has a strange encounter with a priest named Melchizedek. As with Jesus, it comes in a time of sorrow. Abraham faces armed conflict in order to protect his family. The encounter is just as mysterious as the encounter with Veronica.

Melchizedek, king of Salem, brought out bread and wine. He was a priest of God Most High. He blessed Abram with these words: “Blessed be Abram by God Most High, the creator of heaven and earth; And blessed be God Most High, who delivered your foes into your hand.” (Gen 14:18-20 NAB)

The priesthood of the God of Abraham would not be officially established for several hundred more years in the days of Moses and Aaron. What is even more mysterious is the priestly offering of bread and wine, which was not a common offering at the time. This image is familiar to us in our remembrance of Jesus, the Eucharist, which was instituted far in the future for Abraham. In one case, Veronica received a remembrance of Jesus in the image on the cloth she used to wipe the face of Jesus, In the other case, Abraham received a remembrance of Jesus in the substance of the Eucharist. It seems that it is important to Jesus that we remember him.

En la cuarta estación, Jesús se encuentra con su madre. En la historia de Abrahán, no es tanto que Abrahán se encuentre con su madre, sino que trata de encontrar una madre para sus hijos. Dios a menudo le había prometido a Abrahán una descendencia tan numerosa como las estrellas en el cielo, pero la confianza de Abrahán en Dios estaba en tensión con su falta de confianza en su esposa estéril, Sara.

«Señor, respondió Abram, ¿para qué me darás algo, si yo sigo sin tener hijos, y el heredero de mi casa será Eliezer de Damasco?». Después añadió: «Tú no me has dado un descendiente, y un servidor de mi casa será mi heredero». Entonces el Señor le dirigió esta palabra: «No, ese no será tu heredero; tu heredero será alguien que nacerá de ti. (Génesis 15:2-4 LPD)

Abrahán ya había negado que Sara estuviera casada para que los egipcios la arrastraran. Sarah podría estar nerviosa por lo que Abrahán podría hacer a continuación para dejar espacio para una nueva madre. Lo que sucede a continuación solo puede describirse como trágico, especialmente para Agar. Ella tiene su propia via dolorosa. Ya esclava, ahora su sexualidad y procreación son reclamadas como propiedad. Hizo lo que se esperaba de ella, pero su vida solo empeoró. Huyó del abuso solo para que le dijeran que regresara y se sometiera al abuso. Finalmente, una vez que Abrahán conoce a su verdadera madre, es decir, la madre de su heredero, Agar es desechable.

A la madrugada del día siguiente, Abrahán tomó un poco de pan y un odre con agua y se los dio a Agar; se los puso sobre las espaldas, y la despidió junto con el niño. (Génesis 21:14 LPD)

Uno de mis pasatiempos es ir de mochilero, y me encanta ir de mochilero en el desierto. He viajado con mochila en el desierto del Sinaí, el desierto de Judea y aquí en Texas en el Parque Nacional Big Bend. Como mínimo, uno necesita llevar un galón de agua por día para sobrevivir en el desierto, e incluso eso puede ser peligroso en un día caluroso. Despedir a una madre y a su hijo sin más que un odre de agua es una sentencia de muerte. Fue suficiente para perderla de vista antes de morir.

Ella partió y anduvo errante por el desierto de Berseba. Cuando se acabó el agua que llevaba en el odre, puso al niño debajo de unos arbustos, y fue a sentarse aparte, a la distancia de un tiro de flecha, pensando: «Al menos no veré morir al niño». (Génesis 21:14-16 LPD)

No puedo ver morir a mi hijo. Esas palabras nos devuelven a María en la Vía Dolorosa. ¿Qué fuerza tuvo María para estar con su hijo mientras cargaba la cruz? ¿Qué fuerza tuvo María para estar al pie de la cruz mientras él moría? ¿Qué fuerza tuvo María para asumir en ese momento la responsabilidad de convertirse en madre de la Iglesia, comenzando por Juan? ¿Qué fuerza tiene María para escucharnos cada vez que decimos el Ave María y le pedimos que esté con nosotros en la hora de nuestra muerte? Ha estado con muchos hijos cuando muere. La Vía Dolorosa de Agar nos muestra los dolores de María, nuestra madre, a quien todos encontramos cerca de la hora de nuestra muerte.

At station four Jesus meets his mother. In the Abraham story, it’s not so much that Abraham meets his mother as it is that Abraham tries to meet a mother for his children. God had often promised Abraham descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky, but Abraham’s confidence in God was in tension with his lack of confidence in his barren wife, Sarah.

But Abram said, “Lord GOD, what can you give me, if I die childless and have only a servant of my household, Eliezer of Damascus? Look, you have given me no offspring, so a servant of my household will be my heir.” Then the word of the LORD came to him: No, that one will not be your heir; your own offspring will be your heir. (Gen 15:2-4 NAB)

Abraham had already denied that Sarah was married so that she might be dragged off by the Egyptians. Sarah might be getting nervous about what Abraham might do next to make room for a new mother. What happens next can only be described as tragic, especially for Hagar. She has her own sorrowful way. Already a slave, now her sexuality and procreativity are claimed as property. She did what was expected of her, but her life only got worse. She fled from abuse only to be told to return and submit to abuse. Finally, once Abraham meets his real mother, meaning the mother to his heir, Hagar is disposable.

Early the next morning Abraham got some bread and a skin of water and gave them to Hagar. Then, placing the child on her back, he sent her away. (Gen 21:14 NAB)

One of my hobbies is backpacking, and I love to backpack in the desert. I have backpacked in the Sinai desert, the Judean desert, and right here in Texas in Big Bend National Park. At very minimum, one needs to carry a gallon of water per day to survive in the desert, and even that can be dangerous on a hot day. Sending a mother and child away with no more than a skin of water is a death sentence. It was just enough to get her out of sight before dying.

As she roamed aimlessly in the wilderness of Beer-sheba, the water in the skin was used up. So she put the child down under one of the bushes, and then went and sat down opposite him, about a bowshot away; for she said to herself, “I cannot watch the child die.” As she sat opposite him, she wept aloud. (Gen 21:14-16 NAB)

I cannot watch my child die. Those words bring us back to Mary on the Via Dolorosa. What strength Mary had to be with her son as he carried the cross? What strength Mary had to stand at the foot of the cross while he died? What strength Mary had to take on in that moment the responsibility to become the mother of the Church, starting with John? What strength Mary has to listen to us every time we say the Hail Mary and ask her to be with us at the hour of our death? So many children she has been with when they die. Hagar’s Via Dolorosa shows us the sorrows of Mary, our mother, whom we all meet near the hour of our death.

A través de todos los pasos en falso de Abrahán, Dios siempre parece limpiar el desorden. Dios protegió a Sara de Faraón y Abimelec. Dios protegió a Agar e Ismael. Dios está con Abrahán, pero creo que Dios podría tener sentido del humor. Dios afirma la promesa de la descendencia, pero añade la condición de la circuncisión. No recuerdo mi circuncisión cuando era un bebé, pero tenía un amigo que fue circuncidado cuando era adulto. Lo describió como una experiencia claramente desagradable. Ciertamente no es un paso intuitivo si el objetivo es hacer bebés. Para ser honesto, parece una conversación incómoda con el creador del universo. Si eso no fuera lo suficientemente malo, Abrahán tuvo que circuncidar a todos los sirvientes de su casa, que son bastantes si sumamos todos los números de la historia hasta ahora.

Entonces Abrahán tomó a su hijo Ismael y a todos los demás varones que estaban a su servicio–tanto los que habían nacido en su casa como los que había comprado–y aquel mismo día les circuncidó la carne del prepucio, conforme a la orden que Dios le había dado. Cuando fueron circuncidados, Abrahán tenía noventa y nueve años. (Génesis 17:23-24 LPD)

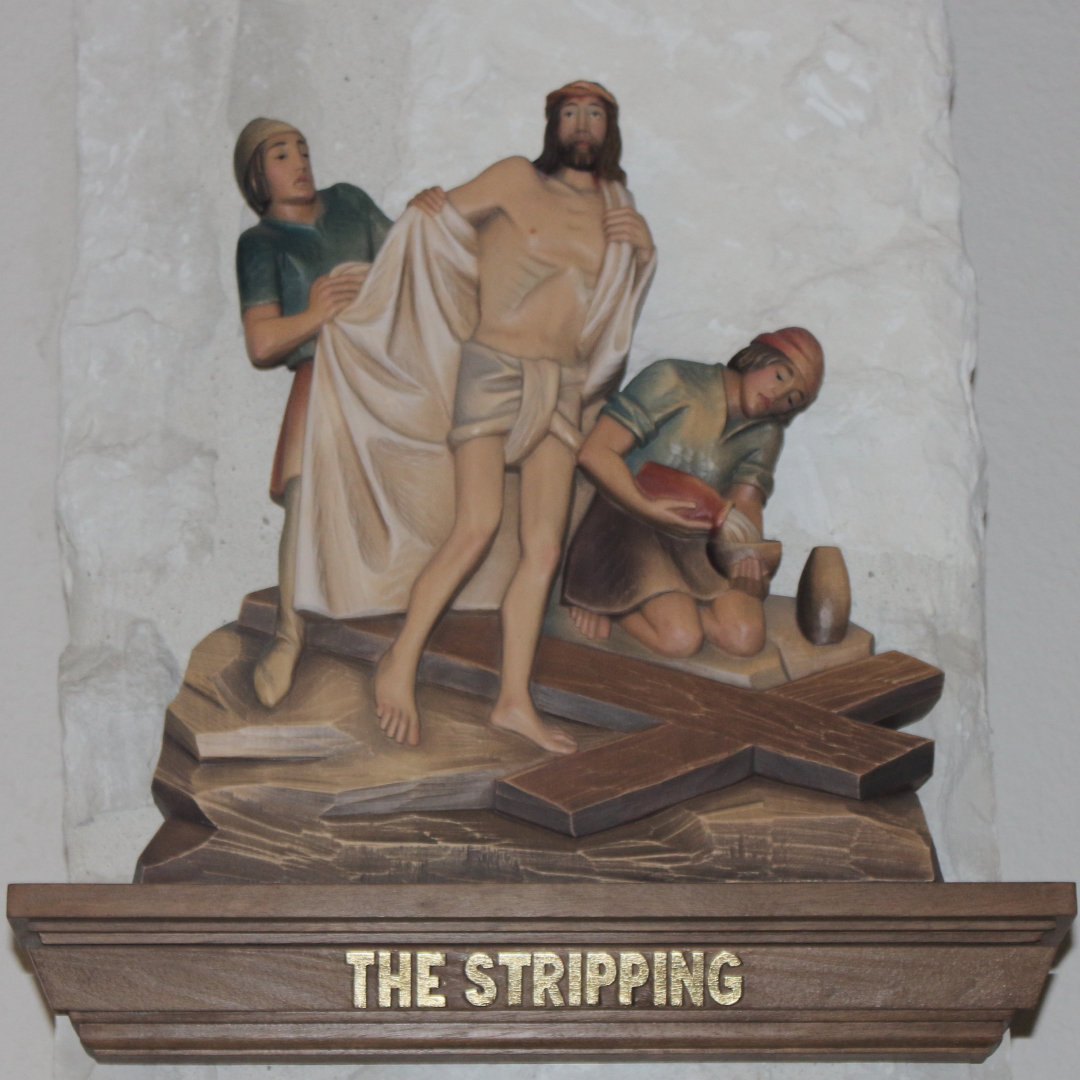

Mientras tanto, en la décima estación, Jesús es despojado de sus vestiduras. Podría sentirme tentado a darle a Abrahán la distinción del camino más doloroso en este punto. O, al menos, lo haría si el punto fuera solo vergüenza. Jesús ya nos había advertido que las necesidades de todas las personas están conectadas a Jesús. Cuando las naciones son juzgadas, algunos dicen: “Señor, ¿cuándo te vimos hambriento o sediento o forastero o desnudo o enfermo o en la cárcel, y no atendemos tus necesidades?” (Mateo 25:44) No es solo Jesús el que es despojado de sus vestiduras, sino todos los más pequeños entre nosotros. No podemos negar la realidad de la pobreza y la privación injusta cuando estamos en la décima estación. Si estamos tristes e indignados porque Jesús está privado, debemos recordar que Jesús nos dijo que sintiéramos lo mismo por los más pequeños entre nosotros.

Through all of Abraham’s missteps, God always seems to clean up the mess. God protected Sarah from Pharaoh and Abimelech. God protected Hagar and Ishmael. God stands with Abraham, but I think God might have a sense of humor. God affirms the promise of descendants, but adds the condition of circumcision. I have no recollection of my circumcision as an infant, but I had a friend who was circumcised as an adult. He described it as a distinctly unpleasant experience. It certainly is not an intuitive step if the goal is to make babies. To be honest, it sounds like an awkward conversation to be having with the creator of the universe. If that wasn’t bad enough, Abraham had to go around circumcising all the male servants in his household, which is quite a few if we add up all the numbers in the story so far.

Then Abraham took his son Ishmael and all his slaves, whether born in his house or acquired with his money—every male among the members of Abraham’s household—and he circumcised the flesh of their foreskins on that same day, as God had told him to do. Abraham was ninety-nine years old when the flesh of his foreskin was circumcised. (Gen 17:23-24 NAB)

Meanwhile, at station ten, Jesus is stripped of his garments. I might be tempted to give Abraham the distinction of the more sorrowful way on this point. Or, at least I would if the point were only shame. Jesus had already warned us that the needs of all people are connected to Jesus. When the nations are judged, some say “Lord, when did we see you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or ill or in prison, and not minister to your needs?” (Matthew 25:44) It is not just Jesus who is stripped of garments but all the least ones among us. We cannot deny the reality of poverty and unjust deprivation when we stand at station ten. If we are sad and indignant that Jesus is deprived, we must remember that Jesus told us to feel the same way about the least among us.

La historia de Abrahán hasta Génesis 17 nos llevó a aproximadamente la mitad de las catorce estaciones de la Vía Dolorosa. La próxima semana continuaremos de la misma manera. Quizás algunos de ustedes vean cómo el resto del viaje de Abrahán nos llevará más allá de las estaciones donde Jesús se encuentra con las mujeres de Jerusalén, es condenado a muerte, toma su cruz, es clavado en la cruz, es bajado de la cruz y es puesto en la tumba. Creo que puede haber algunas sorpresas. Mientras tanto, este es un buen lugar para detenerse y reflexionar sobre las estaciones que ya hemos revisado, nuevamente fuera de secuencia. Comparamos a Abrahán dejando a su familia con la muerte de Jesús. Abrahán le falla a su esposa tres veces como Jesús cae tres veces. Abrahán recibe ayuda extra de Dios a través de personas inesperadas, como Jesús recibe ayuda de Simón de Cirene. Abrahán encuentra un modelo preliminar del recuerdo de Jesús en la Eucaristía, así como Verónica recibe la imagen de Jesús para recordarlo. Abrahán busca una madre para su heredero, como Jesús se encuentra con su madre. Abrahán es despojado de su prepucio, como Jesús es despojado de sus vestiduras. Espero que esto agregue algo a su caminar por la Vía Dolorosa de Jesús esta noche. Recuerden, los dolores de Jesús hacen cumplir las escrituras y dan sentido a nuestro propio dolor.

Abraham’s story up through Genesis 17 brought us to about half of the fourteen stations of the Via Dolorosa. Next week we will continue in the same way. Perhaps some of you see how the remainder of Abraham’s journey will bring us past the stations where Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem, is condemned to death, takes up his cross, is nailed to the cross, is taken down from the cross, and is laid in the tomb. I think there might be some surprises. Meanwhile, this is a good place to stop and reflect on the stations we have already visited, again out of order. We compared Abraham leaving his family to the death of Jesus. Abraham fails his wife three times as Jesus falls three times. Abraham receives some extra assistance from God through unexpected people, as Jesus receives help from Simon of Cyrene. Abraham encounters a preliminary model of the remembrance of Jesus in the Eucharist, as Veronica receives the image of Jesus with which to remember him. Abraham searches for a mother for his heir, as Jesus meets his mother. Abraham is stripped of his foreskin, as Jesus is deprived of his garments. I hope this will add something to your walking the Via Dolorosa of Jesus this evening. Remember, the sorrows of Jesus fulfill the scriptures and give meaning to our own sorrow.