Traducción de Gerardo Yvan Morales

Esta noche me gustaría continuar con el tema que comencé la semana pasada. Estoy comparando la Vía Dolorosa de Jesús con la historia de Abrahán en el Libro del Génesis. Esta comparación muestra cómo lo Nuevo cumple lo Antiguo, cómo el plan de Dios manifestado en Cristo encarnado ya se puede ver en las antiguas escrituras. La comparación también muestra cómo, con algunos ajustes por pequeños detalles, el tema de cómo el sufrimiento encuentra significado en el plan de Dios también se aplica a nuestros dolores. Estoy siguiendo el orden de la historia de Abrahán, lo que significa que estoy saltando de estación en estación en la Vía Dolorosa de Cristo. La semana pasada vimos cómo la muerte de Jesús se compara con la partida de Abrahán de su familia y su tierra natal. Vimos cómo las tres caídas de Jesús se comparan con los tres fracasos de Abrahán para proteger a su esposa. Vimos cómo la ayuda involuntaria de Simón de Cirene es paralela a Faraón y Abimelec en Génesis ofreciendo ayuda inesperadamente. Vimos cómo el don de la imagen de Jesús que recibió Verónica para recordarlo corresponde a la imagen de la Eucaristía, el recuerdo de Jesús, que Abrahán recibió de Melquisedec. Vimos cómo el encuentro de Jesús con su madre se compara con el esfuerzo inapropiado de Abrahán por encontrar una madre para sus hijos. Vimos cómo Jesús despojado de sus vestiduras se compara con Abrahán despojado de su prepucio.

Tonight I would like to continue the theme I began last week. I am comparing Jesus’ Via Dolorosa to the story of Abraham in the Book of Genesis. This comparison shows how the New fulfills the Old, how God’s plan made manifest in Christ incarnate can already be seen in the ancient scriptures. The comparison also shows how, with a few adjustments for small details, the theme of how suffering finds meaning in God’s plan applies to our sorrows as well. I am following the order of the story of Abraham, which means I am jumping around from station to station on Christ’s Via Dolorosa. Last week we saw how the death of Jesus compares to Abraham’s departure from his family and homeland. We saw how the three falls of Jesus compare to the three failures of Abraham to protect his wife. We saw how Simon of Cyrene’s unwilling assistance parallels Pharaoh and Abimelech in Genesis offering assistance unexpectedly. We saw how the gift of Jesus’ image that Veronica received to remember him corresponds to the image of the Eucharist, the remembrance of Jesus, that Abraham received from Melchizedek. We saw how Jesus’ meeting his mother compares to Abraham’s misplaced effort to find a mother for his children. We saw how Jesus stripped of his garments compares to Abraham stripped of his foreskin.

El próximo capítulo en la vida de Abrahán es paralelo a Jesús saludando a las mujeres de Jerusalén, octava estación. Abrahán también se encuentra con tres extraños y les muestra hospitalidad, solo que en lugar de que el Señor salude a tres mujeres, Abrahán saluda al Señor, visto como tres personas.

El Señor se apareció a Abrahán junto al encinar de Mamré, mientras él estaba sentado a la entrada de su carpa, a la hora de más calor. Alzando los ojos, divisó a tres hombres que estaban parados cerca de él. Apenas los vio, corrió a su encuentro desde la entrada de la carpa y se inclinó hasta el suelo. diciendo: «Señor mío, si quieres hacerme un favor, te ruego que no pases de largo delante de tu servidor. Yo haré que les traigan un poco de agua. Lávense los pies y descansen a la sombra del árbol. Mientras tanto, iré a buscar un trozo de pan, para que ustedes reparen sus fuerzas antes de seguir adelante. ¡Por algo han pasado junto a su servidor!». Ellos respondieron: «Está bien. Puedes hacer lo que dijiste». (Génesis 18:1-5 LPD)

Este pasaje también es misterioso en varios sentidos. No está claro cuándo Abrahán reconoció a Dios en estas tres personas. El ofrecimiento de comida y bebida implica hospitalidad a los mortales necesitados. Los extraños continúan sabiendo y prediciendo cosas imposibles sobre Abrahán y Sara. Saben su nombre y predicen que dará a luz mucho después de la menopausia. Abrahán deja entrever que ha descubierto que uno de los visitantes es el juez del universo, pero solo en una frase que desafía la misericordia del juez.

¡Lejos de ti hacer semejante cosa! ¡Matar al justo juntamente con el culpable, haciendo que los dos corran la misma suerte! ¡Lejos de ti! ¿Acaso el Juez de toda la tierra no va a hacer justicia? (Génesis 18:25 LPD)

Abrahán se da cuenta de que no está brindando hospitalidad a extraños necesitados, sino encontrándose con el juez del mundo. En ese momento encuentra el coraje para desafiar a Dios. ¿Es esa una forma de hablar con el creador del universo? Tal vez lo sea. Tal vez desafiar a Dios de vez en cuando, o al menos hacer preguntas difíciles, es parte del viaje de fe.

Como cristianos que leemos Génesis 18, reconocemos a las tres personas que se le aparecen a Abrahán como Dios. Los llamamos la Trinidad. En Génesis 18 Abrahán encuentra a Dios en tres personas. En la Vía Dolorosa, Dios y el hombre (es decir, Cristo) encuentran a Dios en tres personas. La cristología puede resultar confusa. Es demasiado tarde un viernes por la noche para la cristología. Tal vez sea suficiente recordar que para cada mujer y hombre que conocemos, no importa lo que estemos pasando, no importa lo que ellos estén pasando, la Escritura y la Tradición nos muestran qué hacer. Debemos encontrar a Dios en ellos. Y debemos encontrar humanidad en ellos. Tal vez incluso podamos ayudarlos a encontrar su propia dignidad humana e imagen divina. Es todo muy duro.

The next chapter in the life of Abraham parallels Jesus greeting the women of Jerusalem, station eight. Abraham also encounters three strangers and shows them hospitality, only instead of the Lord greeting three women, Abraham greets the Lord, seen as three persons.

The LORD appeared to Abraham by the oak of Mamre, as he sat in the entrance of his tent, while the day was growing hot. Looking up, he saw three men standing near him. When he saw them, he ran from the entrance of the tent to greet them; and bowing to the ground, he said: “Sir, if it please you, do not go on past your servant. Let some water be brought, that you may bathe your feet, and then rest under the tree. Now that you have come to your servant, let me bring you a little food, that you may refresh yourselves; and afterward you may go on your way.” “Very well,” they replied, “do as you have said.” (Gen 18:1-5 NAB)

This passage is also mysterious in several ways. It is not clear when Abraham recognized God in these three people. The offer of food and drink implies hospitality to mortals in need. The strangers go on to know and predict impossible things about Abraham and Sarah. They know her name and predict that she will give birth well past menopause. Abraham lets on that he has figured out that one of the visitors is the judge of the universe, but only in a sentence that challenges the mercy of the judge.

Far be it from you to do such a thing, to kill the righteous with the wicked, so that the righteous and the wicked are treated alike! Far be it from you! Should not the judge of all the world do what is just? (Gen 18:25 NAB)

Abraham realizes he is not providing hospitality to strangers in need, but encountering the judge of the world. In that moment he finds the courage to challenge God. Is that any way to talk to the creator of the universe? Maybe it is. Maybe challenging God every now and then, or at least asking hard questions, is part of the faith journey.

As Christians reading Genesis 18, we recognize the three persons who appear to Abraham as God. We call them the Trinity. In Genesis 18 Abraham finds God in three persons. On the Via Dolorosa God and human (i.e. Christ) finds God in three persons. Christology can get confusing. It’s too late on a Friday evening for Christology. Maybe it is enough to remember that for every woman and man that we meet, no matter what we are going through, no matter what they are going through, Scripture and Tradition shows us what to do. We are to find God in them. And we are to find humanity in them. Maybe we can even help them find their own human dignity and divine image. It is all very hard.

El padre de mi madre murió cuando ella tenía diez años. Cuando yo tenía unos treinta y cinco años, la edad que tenía él cuando murió, mi madre me dijo: “Cuando murió mi padre, todos decían lo triste que era para nosotras las niñas perder a un padre. Ahora que tienes la edad que tenía mi padre cuando murió, pienso en lo duro que fue para mi abuela perder a un hijo”. Es duro perder un hijo.

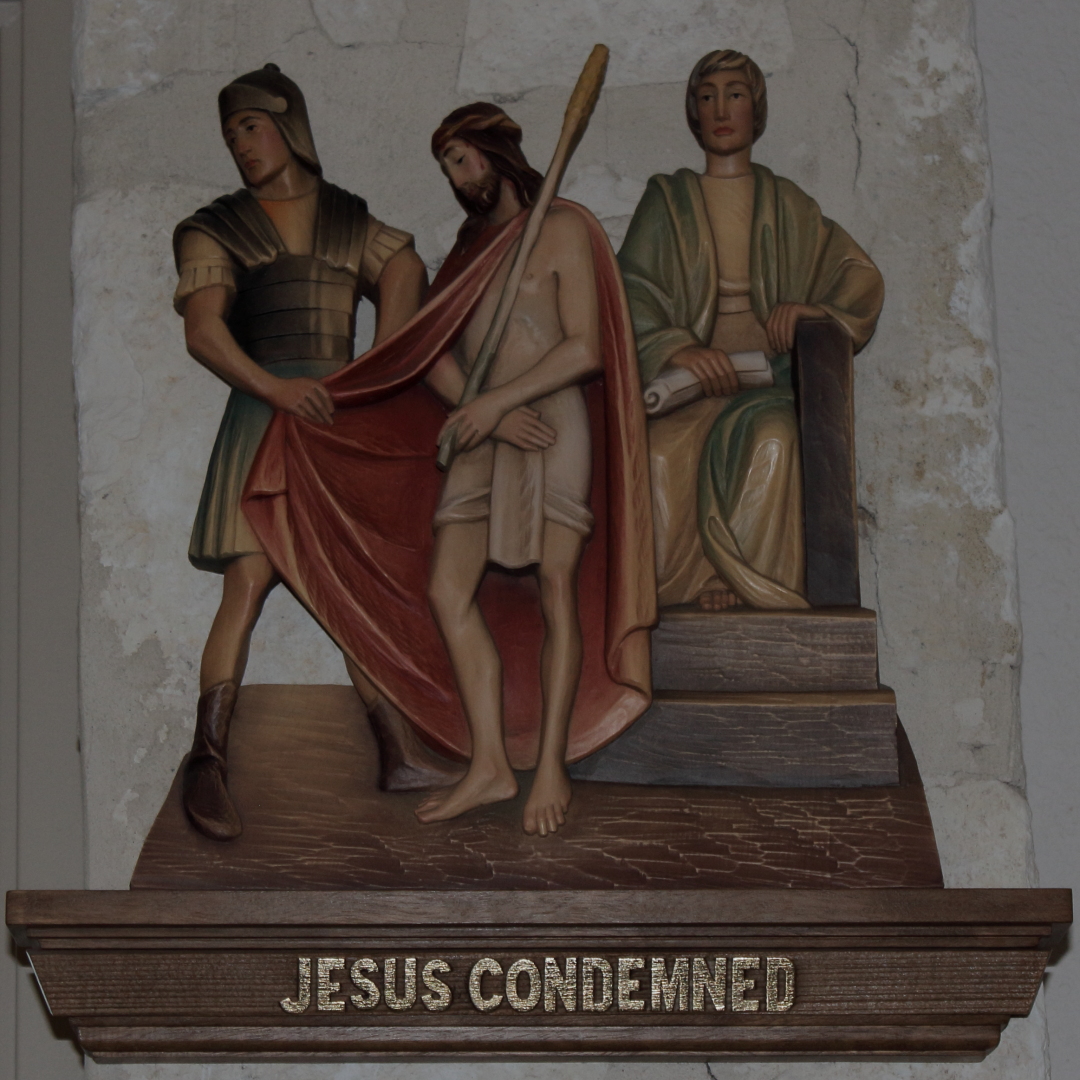

Cuando iniciamos la Vía Dolorosa, la primera estación es Jesús es condenado a muerte. Usamos la voz pasiva para evitar la dura pregunta de quién condenó a muerte a Jesús. Espero que todos ya hayamos aprendido que la vieja mentira de que los judíos mataron a Jesús es teológica e históricamente incorrecta. Puede ser históricamente más correcto decir que Poncio Pilato o los romanos condenaron a muerte a Jesús. Pero eso es teológicamente incorrecto. Los romanos no tenían poder sobre Jesús con sus estúpidas espadas y soldados. En el Huerto de Getsemaní, Jesús lo deja claro, y también que es la voluntad de su padre que muera. Jesús es condenado por su padre a muerte. Que duro es perder un hijo. Que duro es matar a un hijo. Dios sabe cómo debe ser eso. Dios sabe cómo fue eso. Abrahán se acerca.

Después de estos acontecimientos, Dios puso a prueba a Abrahán: «¡Abrahán!», le dijo. El respondió: «Aquí estoy». Entonces Dios le siguió diciendo: «Toma a tu hijo único, el que tanto amas, a Isaac; ve a la región de Moria, y ofrécelo en holocausto sobre la montaña que yo te indicaré». (Génesis 22:1-2 LPD)

Las pruebas en mis clases son mucho más fáciles. ¿Por qué Dios siquiera propondría tal prueba? ¿Qué tuvo que probar Abrahán? ¿Qué tenía Dios que enseñarle a Abrahán? ¿Qué tiene Dios que enseñarnos? Entre otras cosas, tal vez deberíamos pensar en la Vía Dolorosa no sólo como el sufrimiento de Jesús, sino como el sufrimiento del Padre. El Padre condenó a muerte a su Hijo. Cuando Dios el Padre sufre de esta manera, nos apresuramos a decir: “Por supuesto, era necesario quitar los pecados del mundo”. Cuando Abrahán sufre de esta manera, podríamos decir: “Por supuesto, era necesario probar su fe. Todo es parte del plan”. Cuando sufrimos incluso una fracción de eso, ¿somos tan rápidos para confiar en Dios? Jesús nos enseñó a orar para que no seamos probados como fueron probados el Padre y Abrahán. Génesis y la Vía Dolorosa nos enseñan que el dolor no es un pozo sino un camino. Conduce a alguna parte. Tiene un significando. Dios sabe cuál puede ser ese significado.

My mother’s father died when she was ten years old. When I was about thirty-five, the age that he was when he died, my mother told me, “When my father died, everyone said how sad it was for us children to lose a parent. Now that you are the age my dad was when he died, I think about how hard it was for my grandma to lose a son.” It is hard to lose a child.

When we start the Via Dolorosa, the first station is Jesus is condemned to death. We use the passive voice to avoid the hard question of who condemned Jesus to death. I hope we have all learned by now that the old lie that the Jews killed Jesus is theologically and historically wrong. It may be more historically correct to say that Pontius Pilate or the Romans condemned Jesus to death. But that is theologically incorrect. The Romans had no power over Jesus with their stupid swords and soldiers. In the Garden of Gethsemane Jesus makes that clear, and also clear that it is his father’s will that he die. Jesus is condemned by his father to death. How hard it is to lose a child. How hard it is to kill a child. God knows what that must be like. God knows what that was like. Abraham comes close.

Some time afterward, God put Abraham to the test and said to him: Abraham! “Here I am!” he replied. Then God said: Take your son Isaac, your only one, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah. There offer him up as a burnt offering on one of the heights that I will point out to you. (Gen 22:1-2 NAB)

The tests in my classes are much easier. Why would God even propose such a test? What did Abraham have to prove? What did God have to teach to Abraham? What does God have to teach us? Among other things, maybe we should think about the Via Dolorosa not only as the suffering of Jesus, but the suffering of the Father. The Father condemned his Son to death. When God the Father suffers in this way, we are quick to say, “Of course, it was necessary to take away the sins of the world.” When Abraham suffers in this way, we might say, “Of course, it was necessary to prove his faith. It is all part of the plan.” When we suffer even a fraction of that, are we as quick to trust God? Jesus taught us to pray that we not be tested as the Father and Abraham were tested. Genesis and the Via Dolorosa teach us that sorrow is not a pit but a path. It leads somewhere. It has a meaning. God knows what that meaning may be.

¿Qué pasa con el hijo? ¿Qué pasa con Isaac? ¿Qué hay de Jesús? En la segunda estación aprendemos que Jesús toma su cruz. No la pasiva de nuevo, que la cruz fue colocada sobre Jesús, sino que Jesús la tomó. Creemos que Jesús estaba dispuesto a obedecer la voluntad de su padre, que Jesús confiaba en su padre. Veamos quién más lleva el leño sobre el que va a ser sacrificado.

Abrahán recogió la leña para el holocausto y la cargó sobre su hijo Isaac; él, por su parte, tomó en sus manos el fuego y el cuchillo, y siguieron caminando los dos juntos. Isaac rompió el silencio y dijo a su padre Abrahán: «¡Padre!». El respondió: «Sí, hijo mío». «Tenemos el fuego y la leña, continuó Isaac, pero ¿dónde está el cordero para el holocausto?». «Dios proveerá el cordero para el holocausto», respondió Abrahán. Y siguieron caminando los dos juntos. (Génesis 22:6-8 LPD)

A menudo se ha observado la similitud entre Isaac cargando la leña de su sacrificio y Jesús cargando el leño de su sacrificio. Hay otras similitudes. El monte Moriah se identifica en otros lugares como Jerusalén, donde Jesús es asesinado. En ambos casos un padre está dispuesto a matar a su único hijo. En ambos casos ocurre en el momento de la Pascua. En ambos casos hay una maraña de espinas de por medio. En ambos casos se sacrifica una especie de oveja, ya sea un carnero o un cordero. Pero, ¿e Isaac? ¿Isaac estaba dispuesto a ser sacrificado como Jesús? ¿Entiende Isaac aquí lo que el lector entiende aquí, que aquel provisto por Dios para ser sacrificado no es otro que el mismo Isaac? Podemos mirar esa frase, “entonces los dos caminaron juntos”. A menudo, en la Biblia y en varias expresiones idiomáticas, caminar juntos significa estar de acuerdo. La palabra inglesa “concur” (estar de acuerdo) significa literalmente correr con (correr en el sentido de un río que corre es una corriente o que la electricidad que fluye es una corriente). Cuando Enoc y otros héroes bíblicos caminan con Dios, entendemos que eso significa una alineación de propósito. Cuando Isaac caminó con Abrahán, tal vez eso no signifique que fue engañado, sino que él, como Jesús, estuvo de acuerdo con la voluntad de Dios. También es interesante notar que si sumamos las edades en las historias circundantes, Isaac tendría aquí treinta y siete años frente a los ciento treinta y siete años de su padre. Si Isaac no hubiera querido, sospecho que podría haberse enfrentado al anciano y al menos haber escapado.

Pero si Isaac estaba dispuesto, ¿en qué estaba pensando? ¿Confiaba en su padre? ¿Confía en Dios? ¿Reconoció que haber sido “provisto por Dios” viene con ciertas condiciones? ¿Un favor que se puede reclamar en cualquier momento? ¿Reconoció que su vida o toda la vida es un regalo para experimentar por un tiempo pero no poseer y conservar en un estante? Hubo otros mártires que entendieron que la vida es santa, pero no la santísima. Hay un bien y un propósito superior incluso sobre la vida terrenal misma. Espero que nadie aquí se convierta nunca en un mártir, pero espero que todos aquí entiendan por qué la fe cristiana honra a los mártires. La vida es un regalo, la felicidad es un regalo, nuestro tiempo juntos es un regalo. Sin embargo, son regalos de Dios, un Dios que sabe que hay un bien superior incluso a esas cosas buenas. Solo Dios dura para siempre.

What about the son? What about Isaac? What about Jesus? At station two we learn that Jesus takes up his cross. Not the passive again, that the cross was placed on Jesus, but that Jesus took it up. We believe Jesus was willing to obey the will of his father, that Jesus trusted his father. Let us see who else carries the wood on which he is to be sacrificed.

So Abraham took the wood for the burnt offering and laid it on his son Isaac, while he himself carried the fire and the knife. As the two walked on together, Isaac spoke to his father Abraham. “Father!” he said. “Here I am,” he replied. Isaac continued, “Here are the fire and the wood, but where is the sheep for the burnt offering?” “My son,” Abraham answered, “God will provide the sheep for the burnt offering.” Then the two walked on together. (Gen 22:6-8 NAB)

The similarity between Isaac carrying the wood of his sacrifice and Jesus carrying the wood of his sacrifice has often been observed. There are other similarities. Mount Moriah is elsewhere identified as Jerusalem, where Jesus is killed. In both cases a father is willing to kill his only son. In both cases it happens at the time of Passover. In both cases there is a thicket of thorns involved. In both cases a kind of sheep, either a ram or a lamb, is sacrificed. But what about Isaac? Was Isaac willing to be sacrificed as Jesus was? Does Isaac understand here what the reader understands here, that the one provided by God to be sacrificed is none other than Isaac himself? We can look at that phrase, “then the two walked on together.” Often in the Bible and various idioms, to walk together means to agree. The English word “concur” (to agree) literally means to run with (run in the sense of a river running is a current or flowing electricity is a current). When Enoch and other biblical heroes walk with God we understand that to mean an alignment of purpose. When Isaac walked with Abraham, maybe that means not that he was duped, but that he, like Jesus, agreed to God’s will. It is also interesting to note that if we add up the ages in the surrounding stories, Isaac would be here thirty-seven years old to his father’s one-hundred-thirty-seven years. If Isaac was not willing I suspect he could have taken on the old man and at least escaped.

But if Isaac was willing, what was he thinking? Did he trust his father? Did he trust God? Did he recognize that having been “provided by God” comes with certain conditions? A favor that can be called in at any moment? Did he recognize that his life or all life is a gift to experience for a time but not own and preserve on a shelf? There were other martyrs who understood that life is holy, but not the most holy. There is a higher good and purpose even over earthly life itself. I hope no one here ever becomes a martyr, but I hope that everyone here understands why the Christian faith honors martyrs. Life is a gift, happiness is a gift, our time together is a gift. Yet, they are gifts from God, a God who knows that there is a higher good even than those good things. Only God lasts forever.

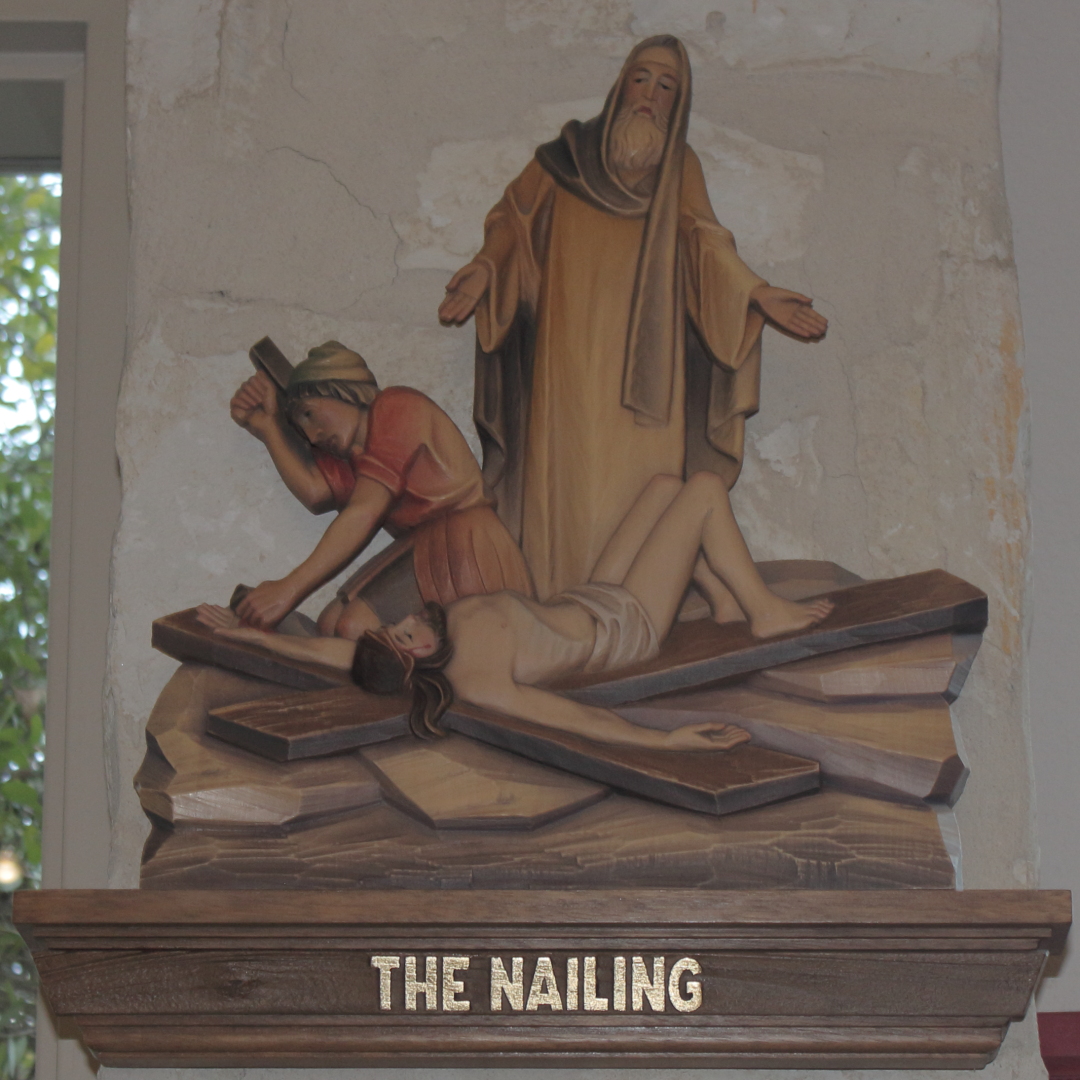

En la onceava estación, la sentencia de muerte declarada en la primera estación se vuelve más inmediata. Jesús es clavado en el madero de la cruz. No hay vuelta atrás. Cualquiera que sea la dignidad que se haya encontrado en caminar voluntariamente, ahora se entrega a la total impotencia. Con Abrahán e Isaac, no hay romanos que confundan el cuadro. Sólo están los elementos cruciales. Hay un padre dispuesto a matar a su hijo. Está el hijo, todavía dispuesto, sin protestar, ahora privado de poder. Hay madera. Hay un cuchillo para matar más rápido que los clavos. Hay un sacrificio.

Cuando llegaron al lugar que Dios le había indicado, Abrahán erigió un altar, dispuso la leña, ató a su hijo Isaac, y lo puso sobre el altar encima de la leña. Luego extendió su mano y tomó el cuchillo para inmolar a su hijo. (Génesis 22:9-10 LPD)

El lugar del que Dios le había dicho es ahora el lugar donde están. Eso es todo. Tal vez todo parecía más fácil como una noción abstracta. Sí, amamos a los mártires. Sí, admiramos a los que se sacrifican. Sí, aquellos que renuncian a su libertad por una causa son tales héroes. Ahora es el momento. Ahora somos nosotros. ¿Se ve diferente ahora?

At station eleven the death sentence declared at station one becomes more immediate. Jesus is nailed to the wood of the cross. There is no going back. Whatever dignity may have been found in walking willingly is now given over to utter powerlessness. With Abraham and Isaac, there are no Romans to confuse the picture. There are only the crucial elements. There is a father willing to kill his son. There is the son, still willing, not protesting, now deprived of power. There is wood. There is a knife to kill more quickly than nails. There is a sacrifice.

They came to the place of which God had told him. Abraham built an altar there and arranged the wood on it. He bound his son Isaac. He put him on top of the wood on the altar. Abraham reached out and took the knife to slaughter his son. (Gen 22:9-10 NAB slightly adapted)

The place of which God had told him is now the place where they are. This is it. Maybe everything seemed easier as an abstract notion. Yes, we love martyrs. Yes, we admire those who sacrifice themselves. Yes, those who give up their freedom for a cause are such heroes. Now is the moment. Now it is us. Does it look different now?

Las historias, antes tan parecidas, ahora divergen. Jesús es bajado del madero muerto. Isaac se salva. Solo fue una representación. Por mucho que Dios quiera que contemplemos el significado del sufrimiento y la muerte como parte del plan de Dios, Dios en realidad no le desea eso a nadie más. La muerte de Jesús es única en ese sentido. Abrahán sufre pero no mata, como Dios Padre. Isaac sufre voluntariamente pero no muere, como lo hace Dios el Hijo. Sufrimos pero no tan completamente como lo hace Dios.

¿Qué hay de Abrahán? ¿Abrahán lo entiende? ¿Abrahán entiende por qué tuvo que pasar por todo eso? ¿Abrahán ve como nosotros que era un preámbulo de otro sacrificio por venir?

Al levantar la vista, Abrahán vio un carnero que tenía los cuernos enredados en una zarza. Entonces fue a tomar el carnero, y lo ofreció en holocausto en lugar de su hijo. Abrahán llamó a ese lugar: «El Señor proveerá», y de allí se origina el siguiente dicho: «En la montaña del Señor se proveerá». (Génesis 22:13-14 LPD)

Dios proveerá. El verbo no es pasado sino futuro. No es que Dios haya provisto a Isaac o un carnero, sino que proveerá en el futuro el sacrificio perfecto. Un carnero es una oveja macho adulta. Un cordero es una oveja joven. Los intérpretes cristianos han entendido la visión del futuro de Abrahán como el cordero de Dios con la corona de espinas es como la del carnero con los cuernos enredados en la zarza. Solo ese sacrificio es el sacrificio perfecto que toma el lugar de Isaac y todos los sacrificios de animales. Lo nuevo está escondido en lo viejo, pero podemos encontrarlo si miramos con atención. Cuando estudiamos el Antiguo Testamento y buscamos paralelos con el Nuevo Testamento, vemos que todo es paralelo. Cuando vemos que todo es paralelo en la historia de la salvación de Dios, vemos que nuestras vidas, incluso en los momentos de dolor, son paralelas al plan de Dios cuando estamos dispuestos a ver las cosas de esa manera.

The stories, so similar before, now diverge. Jesus is taken down from the wood dead. Isaac is spared. It was a dry run. As much as God wants us to contemplate the meaning of suffering and death as part of God’s plan, God does not actually wish that on anyone else. The death of Jesus is unique in that way. Abraham suffers but does not kill, as does God the Father. Isaac suffers willingly but does not die, as does God the Son. We suffer but not as completely as does God.

What about Abraham? Does Abraham get it? Does Abraham understand why he had to go through all that? Does Abraham see as we do that it was a preview of another sacrifice to come?

Abraham looked up and saw a single ram caught by its horns in the thicket. So Abraham went and took the ram and offered it up as a burnt offering in place of his son. Abraham named that place Yahweh-yireh; hence people today say, “On the mountain the LORD will provide.” (Gen 22:13-14 NAB)

God will provide. The verb is not past but future. It is not that God has provided Isaac or a ram, but will provide in the future the perfect sacrifice. A ram is an adult male sheep. A lamb is a young sheep. Christian interpreters have understood Abraham’s vision of the future as the lamb of God with the crown of thorns like the ram’s head in a thicket. Only that sacrifice is the perfect sacrifice that takes the place of Isaac and all animal sacrifices. The new is hidden in the old, but we can find it if we look carefully. When we study the Old Testament and look for parallels to the New Testament, we see that everything is parallel. When we see that everything is parallel in the story of God’s salvation, we see that our lives, even in the sorrowful times, are parallel with God’s plan when we are willing to see things that way.

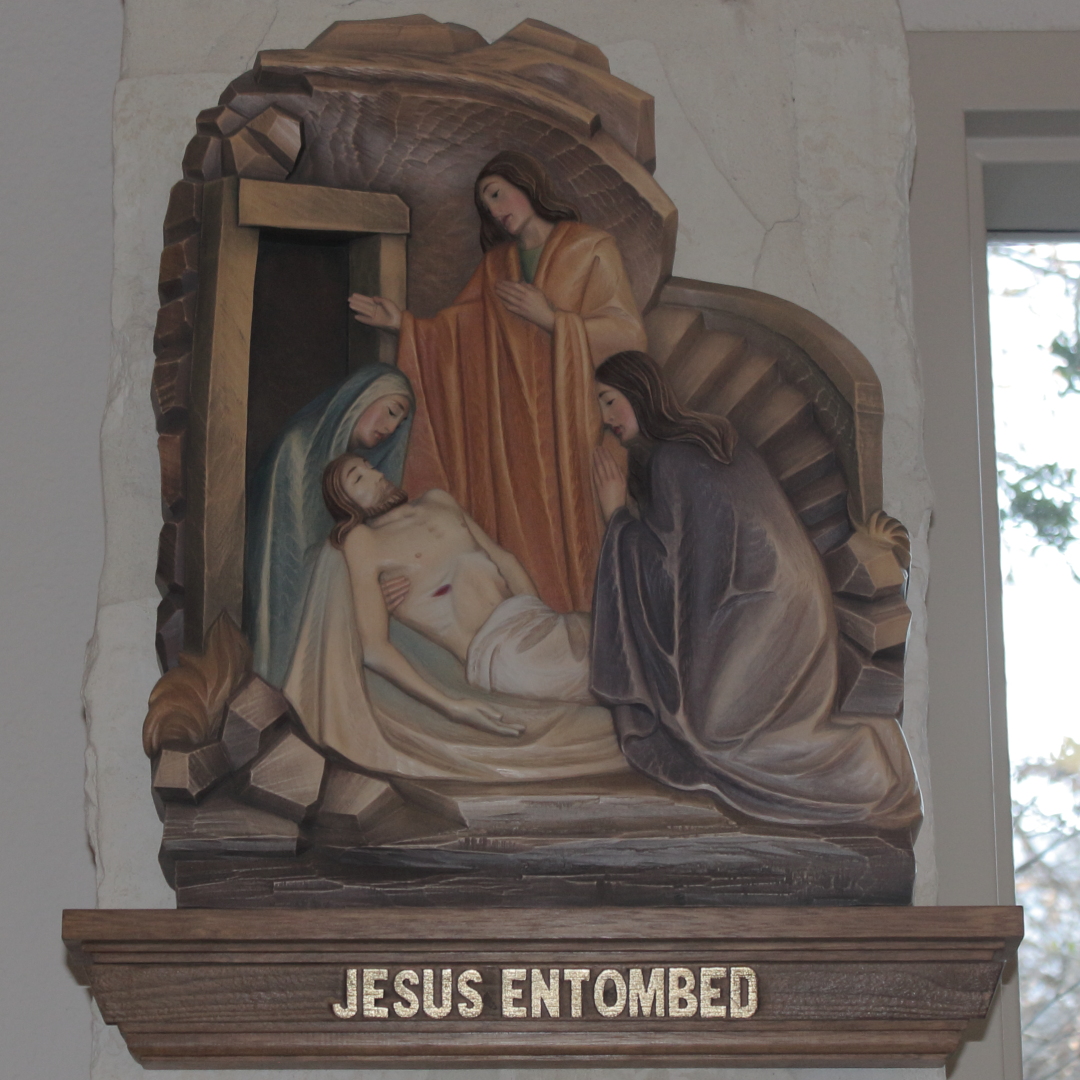

Los intérpretes antiguos afirmaron que Abrahán soportó muchas pruebas, no solo la prueba explícita en el capítulo veintidós de Génesis. De hecho, la prueba de su hijo no es la última. Hay una más. Nosotros también tenemos una estación más para visitar. La última de nuestras estaciones es la catorce, Jesús es puesto en la tumba. Isaac pudo haberse salvado. Abrahán pudo haber previsto el sacrificio perfecto que quita los pecados del mundo. Aquí estamos después de Jesús. Si Jesús ha quitado los pecados del mundo, ¿por qué todavía experimentamos la muerte? ¿Por qué todavía tenemos que enterrar a nuestros seres queridos? Creemos que la muerte no es el final de la historia, pero es parte de la historia.

Sara vivió ciento veintisiete años, y murió en Quiriat Arbá –actualmente Hebrón– en la tierra de Canaán. Abrahán estuvo de duelo por Sara y lloró su muerte. Después se retiró del lugar donde estaba el cadáver, y dijo a los descendientes de Het: «Aunque yo no soy más que un extranjero residente entre ustedes, cédanme en propiedad alguno de sus sepulcros, para que pueda retirar el cadáver de mi esposa y darle sepultura». (Génesis 23:1-4 LPD)

El resto del capítulo continúa como algo así como la planificación funeraria inversa. Los lugareños quieren darle a Abrahán la cueva como lugar de entierro, tal vez como Nicodemo deseaba enterrar a Jesús. Para Abrahán es importante que pague por ello, que no se lo den. ¿Por qué es eso tan importante? La historia de Abrahán comenzó en el capítulo doce con la promesa de Dios de tierra y descendencia.

El Señor se apareció a Abram y le dijo: «Yo daré esta tierra a tu descendencia». (Génesis 12:7 LPD)

La promesa de los descendientes se ve bastante bien con Isaac sobreviviendo a la prueba. Abrahán nota dos problemas con los habitantes locales que le dan a Abrahán incluso un terreno para sepultura. Primero, Dios da la tierra, no otras personas. No es de ellos para dar. Toda la tierra pertenece a Dios. Sólo la estamos ocupando. Segundo, Abrahán reconoce que la tierra no es para que él la reciba. Dios dijo que la tierra es para las generaciones futuras, no para su generación. Eso puede decirnos cómo tratar el medio ambiente. También puede decirnos algo acerca de Dios. Dios parece trabajar lentamente en relación con nuestras expectativas. El salmo noventa dice que mil años para Dios es como un día para nosotros. Ciertamente puede parecer que Dios está tardando mil años en hacer lo que queremos que se haga hoy. Pasaron casi dos mil años desde Abrahán hasta Jesús. Pasaron cuatro mil años para que los esclavos que Abrahán aceptó fueran liberados. Jesús está tardando más de dos mil años en regresar en gloria. Puede parecer que el racismo nunca terminará. No pretendo entender por qué Dios espera tanta paciencia de nosotros. Sé que Dios nos explicó en las Escrituras que la satisfacción inmediata no es parte de la promesa. Abrahán reconoció que la promesa de la tierra era un proyecto que tomaría más tiempo. Moisés reconoció que la herencia de la tierra no era para su generación. Martin Luther King Junior, en su último discurso, sabía exactamente lo que quería decir Moisés. El último final de la muerte no es para nuestra generación. Pondremos a nuestros seres queridos en la tumba, como hicimos con Sara, como hicimos con Jesús. Terminaremos nuestro doloroso camino con la esperanza de la victoria de la vida sobre la muerte. Las promesas de Dios son seguras, pero el tiempo de Dios no es para que lo decidamos nosotros. Dentro de tres días, o dentro de tres milenios, nos levantaremos.

Ancient interpreters asserted that Abraham endured many tests, not just the one test explicit in chapter twenty-two of Genesis. In fact, the binding of his son is not the last test. There is one more. We too have one more station to visit. The last of our stations is fourteen, Jesus is laid in the tomb. Isaac may have been spared. Abraham may have foreseen the perfect sacrifice that takes away the sins of the world. Here we are after Jesus. If Jesus has taken away the sins of the world, why do we still experience death? Why do we still have to bury our loved ones? We believe that death is not the end of the story, but it is part of the story.

The span of Sarah’s life was one hundred and twenty-seven years. She died … in the land of Canaan, and Abraham proceeded to mourn and weep for her. Then he left the side of his deceased wife and addressed the Hittites: “Although I am a resident alien among you, sell me from your holdings a burial place, that I may bury my deceased wife.” (Gen 23:1-4 NAB)

The rest of the chapter continues as something like reverse funeral planning. The locals want to give Abraham the cave as a burial site, perhaps as Nicodemus wished to bury Jesus. It is important to Abraham that he pay for it, that they not give it to him. Why is that so important? The story of Abraham began in chapter twelve with God’s promise of land and descendants.

The LORD appeared to Abram and said: To your descendants I will give this land. (Gen 12:7 NAB)

The promise of descendants is looking pretty good with Isaac surviving the test. Abraham notices two problems with the local inhabitants giving Abraham even a burial plot. First, God gives the land, not other people. It is not theirs to give. All land, all the earth belongs to God. We are just squatting on it. Second, Abraham recognizes that the land is not for him to receive. God said the land is for future generations, not his generation. That can tell us how to treat the environment. It can also tell us something about God. God seems to work slowly relative to our expectations. Psalm ninety says that a thousand years for God is like a day for us. It can certainly feel like God is taking a thousand years to do what we want done today. It took almost two thousand years from Abraham until Jesus. It took four thousand years for the slaves that Abraham accepted to be freed. It is taking more than two thousand years for Jesus to return in glory. It might feel like racism will never end. I don’t claim to understand why God expects so much patience from us. I do know that God explained to us in the scriptures that immediate satisfaction is not part of the promise. Abraham recognized that the promise of the land was a project that would take more time. Moses recognized that the inheritance of the land was not for his generation. Martin Luther King Junior, in his last speech, knew exactly what Moses meant. The final end of death is not for our generation. We will lay our loved ones in the tomb, as we did Sarah, as we did Jesus. We will end our sorrowful way with hope of victory of life over death. God’s promises are sure but God’s timing is not for us to decide. Three days from now, or three millennia from now, we rise.